Wave Wire Services

LOS ANGELES — Fed up by what he considers government inaction, bureaucratic paralysis and a lack of accountability, a federal judge has ordered the city and county of Los Angeles to offer housing to the entire homeless population of downtown’s Skid Row by October.

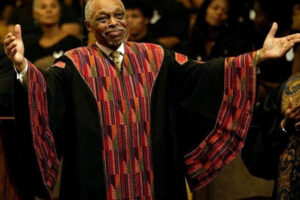

U.S. District Judge David O. Carter set a timetable April 20 by which single women and unaccompanied children must be offered placement within three months, families must be given shelter within four months, and every indigent person on Skid Row would be given the opportunity to come off the streets by Oct. 18.

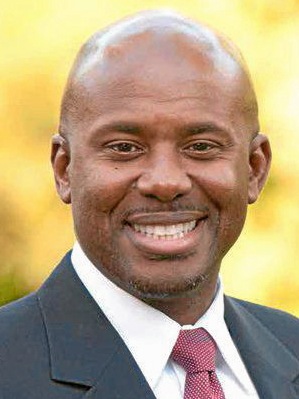

Mayor Eric Garcetti called the timetable “unprecedented” in terms of speed.

“I want to read [the order] and understand how [the judge] would envision that happening, where the rooms, the real estate etc. [are],” Garcetti said. “I’ve had great conversations with the judge. Obviously that would be an unprecedented pace, not just for Los Angeles but for any place I’ve ever seen for homelessness in America. And I want to be as bold and as ambitious as him, but like I said, I think many of us feel it’s not just about getting people into shelter, it’s getting people into homes.”

The groundbreaking 110-page order comes in response to a request for immediate court intervention submitted last week by the plaintiffs in a year-old federal lawsuit seeking to compel the city and county to quickly and effectively deal with the homelessness crisis.

Skid Row is a spread-out 50-block warren of downtown streets containing one of the largest populations of indigent people in the nation.

Skip Miller, outside counsel for the county, said Carter’s order “goes well beyond what the plaintiffs have asked for.” He added that the county was evaluating its options, including the possibility of an appeal to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

The judge wrote that the city and county of Los Angeles “created a legacy of entrenched structural racism,” leaving Black people — and especially Black women – “effectively abandoned on the streets. Such governmental inertia has affected not only Black Angelenos, not only homeless Angelenos, but all Angelenos — of every race, gender identity, and social class.”

The judge said that virtually “every citizen of Los Angeles has borne the impacts of the city and county’s continued failure to meaningfully confront the crisis of homelessness. The time has come to redress these wrongs and finish another measure of our nation’s unfinished work.”

Quoting Heidi Marston, director of the L.A. Homeless Services Authority, the judge wrote that “homelessness is a byproduct of racism.”

In colorful language that takes in the Civil War and the Bruce’s Beach case of forced displacement of Blacks in Manhattan Beach, Carter traced the start of the crisis downtown to the 1920s, when the city created the Municipal Service Bureau for Homeless Men in Skid Row to assist men by connecting them with philanthropic organizations that provided food and lodging.

However, “aid from such organizations was distributed selectively along racial lines,” the judge found, adding that Los Angeles’ highway infrastructure was “built as and remains a driver of racial inequality” by helping to displace and segregate non-white communities.

Near Skid Row now “are thriving neighborhoods — namely the Arts District and Little Tokyo District. As these districts edge closer to the boundaries of containment, police presence within Skid Row grows stronger,” the judge wrote.

Carter’s housing order rejects city and county arguments that federal court intervention would improperly usurp the role of local government and upend longstanding programs already dealing with the crisis.

The motion was filed by the L.A. Alliance for Human Rights, a coalition of downtown business owners and residents that originally brought the lawsuit in March 2020. City and county attorneys strongly objected, arguing in court papers that the L.A. Alliance’s “extraordinary” attempt to invoke the power of the court is “overbroad and unmanageable,” lacks legal standing and would “improperly usurp the role of local government and its elected officials.”

Elizabeth Mitchell, an attorney for L.A. Alliance, said the organization is “thrilled” with Carter’s order, which “takes the first step toward actually solving the homelessness crisis in Los Angeles.”

She said that city and county leaders have repeatedly called for a FEMA-like response — and “the judge is holding them to their word.”

“He’s also demanded accountability in the billions of dollars that are supposed to be used to house the unhoused — who actually aren’t being housed at all,” she said. “The judge has recognized the fact of which nearly every citizen in Los Angeles is already acutely aware: that the status quo isn’t working and cannot be allowed to continue. This order gives us hope that the solutions will finally start outpacing the problems.”

In his order, Carter blasted Garcetti, who recently promised to spend nearly $1 billion on initiatives for addressing homelessness and other issues including sidewalk vending and arts activities. Instead, the judge ordered that the $1 billion “will be placed in escrow forthwith, with funding streams accounted for and reported to the court within seven days.”

Carter wrote that despite the power to declare the homelessness crisis an emergency — which would allow the city to “bypass the bureaucracy and eliminate the inefficiencies that currently stifle progress” — Garcetti “has not employed the emergency powers given to him by the City Charter despite overwhelming evidence that the magnitude of the homelessness crisis is ‘beyond the control of the normal services’ of the city government.”

In his conclusion, Carter said that for all the governmental “declarations of success that we are fed, citizens themselves see the heartbreaking misery of the homeless and the degradation of their city and county. Los Angeles has lost its parks, beaches, schools, sidewalks and highway systems due to the inaction of city and county officials who have left our homeless citizens with no other place to turn.”

All of the “rhetoric, promises, plans and budgeting cannot obscure the shameful reality of this crisis — that year after year, there are more homeless Angelenos, and year after year, more homeless Angelenos die on the streets,” Carter wrote.

County officials believe there are several thousand persons currently living on Skid Row streets. According to the Homeless Services Authority, 1,441 people in the area were temporarily housed last year.

L.A. Alliance lawyers have written that Skid Row is a “catastrophe created by the city and county” in which the city adopted a policy of “physical containment” whereby the poor, disabled and mentally ill would be “contained” inside the delineated borders of Skid Row.

Over the past year, with federal courthouses closed or not fully operational due to the coronavirus pandemic, Carter has held emergency hearings in such locations as Los Angeles City Hall and a women’s shelter in Skid Row.

“Undoubtedly, both the city and county will feel that such an order is diminishing their powers,” the L.A. Alliance said in a statement when it signaled it would seek a preliminary injunction. “Yet, in the absence of a consensual agreement by the parties, court intervention becomes necessary.”

The L.A. Alliance said that after numerous settlement conferences and discussions, “it is clear that the local governments are unable/unwilling to address the problem adequately. The courts must take a more active role.”

Nine days after the lawsuit was filed last year, the parties suspended litigation with the intent to explore a settlement “and set the stage for a comprehensive solution in the city and county of L.A.,” the plaintiffs stated.

Proposed solutions became bogged down in bureaucratic snarls between the city and county, prompting Carter to consider how he might deploy the power of the federal court to speed up efforts to get city sidewalks cleared and place homeless people into housing.