By Phoenix Tso

Contributing Writer

LOS ANGELES — Abril Dozal first got involved with the city’s neighborhood councils by attending the Wilshire Center Koreatown Neighborhood Council’s planning committee meetings.

She was struck by the fact that the neighborhood council could make recommendations directly to the city planner about whether to approve a permit for a development within the council’s boundaries and recommend changes to projects as well.

“They were asking for bike lanes, they were asking for green space, union jobs, things that would help my neighbors and myself, and so after that, I decided to get on the council to participate in those conversations,” Dozal said. She applied for a vacant seat and was appointed by the neighborhood council board last summer.

Neighborhood councils are community-level advisory bodies that offer Angelenos a direct voice in city services and policy. The councils can submit community impact statements in support or opposition to a City Council motion. They also have a limited budget to support nonprofit groups and carry out beautification or capital improvement projects within their districts and advise the mayor and city departments on budget priorities.

Ninety-one of LA’s 99 neighborhood councils are holding elections this year, giving residents an opportunity to participate either as voters or candidates. The elections will take place on 12 different regional timelines from March through mid-June.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the elections are entirely vote-by-mail. Voters have until one week before their council’s election day to request a ballot online or by mail. Once a voter receives a ballot, they have until their election day to fill it out and bring it to a dropbox or to get it postmarked. Candidate filing is still open for some neighborhood council regions.

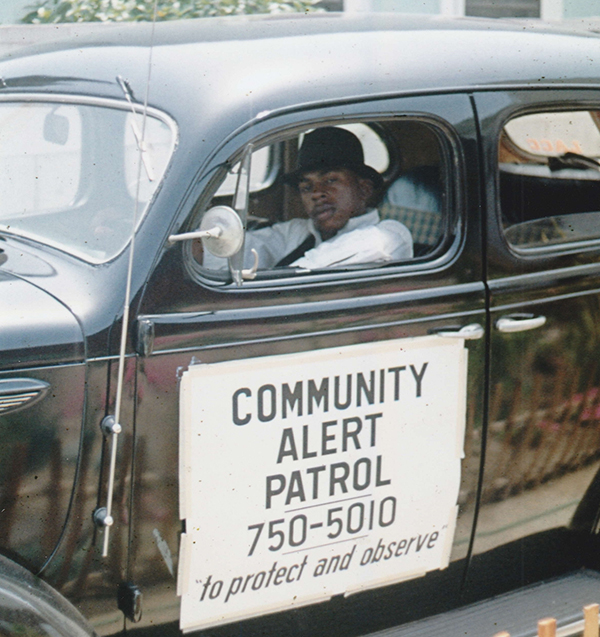

The city formed neighborhood councils in 1999 through a city charter amendment. Officials modeled the councils in part after the Empowerment Congress, which Black leaders in South Los Angeles founded in 1992 to advocate for their community’s needs after riots following the acquittal of four LAPD officers in the brutal beating of Rodney King.

The San Fernando Valley secession movement, which culminated in a failed 2002 ballot measure over whether the region would incorporate as its own city, also inspired the creation of the neighborhood councils.

“It was a wake-up call that the old, strictly centralized municipal government model was not serving Angelenos equitably, given L.A.’s sheer size and considerable cultural diversity,” said Ann-Marie Holman, a public information officer with the Department of Neighborhood Empowerment, also known as EmpowerLA.

There are around 1,800 seats across all 99 neighborhood councils, with the exact makeup and bylaws varying with each council. As a result, the councils reflect the unique nature of their neighborhoods, with some reserving specific seats for renters or even equestrians, and other councils restricting who can vote for certain seats.

Overall there are not as many restrictions on people who can run for and vote in neighborhood councils elections compare to traditional elections. In addition to residents, those who work, own property or a business or who have community interest within a neighborhood council’s boundaries — for example, as students or worshippers or local nonprofit service organizations — can vote if they are 16 or older and run if they are 18 or older. Stakeholders as young as 14 can vote or run for a youth seat, if available. Participation is also open to the formerly incarcerated and those who are not legal U.S. residents.

While neighborhood councils don’t have direct power in implementing city policy, they can have powerful advisory capabilities.

Johnny Echavarria has lived in Boyle Heights for a year and is running for his neighborhood council. If elected, he plans on advocating for the creation of neighborhood council seats for unhoused stakeholders. He also wants to advocate for policies like canceling rent and educational equity, by using the board to give officials like City Councilman Kevin De León, whose district encompasses Boyle Heights, a little push on those issues.

“We want to be unanimous in advising [the] City Council [on] what they should be doing during this time,” Echavarria said.

Last year, the City Council considered a motion that would prohibit unhoused people from sitting, sleeping or lying within 500 feet of a homeless shelter or freeway. Twenty neighborhood councils submitted community impact statements, with most opposing the motion and helping to defeat the measure.

“In collaboration, the neighborhood councils have a lot more say and sway,” Dozal said.

EmpowerLA conducted a combination of in-person and digital outreach for the 2019 neighborhood council elections, turning out around 23,000 people. Almost 350 people attended their in-person candidate information sessions.

This year, outreach will be entirely online, and will include digital advertising and micro-targeted Nextdoor messages. Attendance has already doubled compared to 2019 for candidate info sessions held over Zoom. The department is also engaging in multilingual mass text messaging for communities with limited internet access.

The neighborhood councils can also do their own voter and candidate outreach, with the Wilshire Center Koreatown Neighborhood Council conducting candidate outreach at various community organizations in English, Spanish and Korean, according to Dozal. This has resulted in two monolingual Spanish-language candidates running for seats this year.

People can find their neighborhood council at http://tinycc/FindMyNC and individual election timelines at http://tinycc/2021ncelectiontimelines. Vote-by-mail info and candidate information are available at the City Clerk’s website and candidate info sessions are available at Eventbrite.