By Emily Jo Wharry

Los Angeleno

L.A.’s most devoted roller skaters aren’t young TikTok stars — they’re Angelenos in their 50s, 60s, 70s and beyond. For them, roller-skating never made a comeback because it never left. But with no end to COVID-19 in sight, the few remaining indoor rinks where they gather are in danger of not reopening.

Mathew Owens remembers first picking up roller skates in the late 1950s, when he still lived in his hometown of Dayton, Ohio. As he grew older, military service, marriage and a family vied for his attention, keeping him out of rinks and off his skates for over two decades.

Nearly 50 years later, in 2002, as he packed up his house for a move, he found an aged pair of skates sitting in the back of a garage cabinet. The bearings were shot, the wheels were too wide, and the rubber had cured — but Owens still felt a pull.

“A voice in the back of my head said, ‘Well, maybe I’m supposed to skate again,’” Owens says. “And I took the skates and threw them in the trunk of my car.”

The skates sat in his trunk for weeks until he found himself at the parking lot of Mid-City’s World on Wheels. Owens sat in his car for a while, contemplating his options. He didn’t know much about L.A.’s roller-skating scene, he says, and he was afraid to go in for fear of being too old to be at a rink. But after seeing two men his age walk through the doors, he instinctively grabbed his skates — by the back wheels, the same way he always grabbed them as a kid skating around Dayton — and walked toward the entryway’s music.

“I went in, paid my dough, and put these old beat-up skates on. I think I must’ve skated about a half an hour before they broke. I had to limp off the floor,” Owens laughs. “But that half an hour created a monster. I got them fixed, and I’ve been skating ever since.”

Now 76 years old, Owens is a member of L.A.’s most dedicated community of roller skaters: older adults in their 50s, 60s, 70s and beyond who meet up to skate multiple times every week. They’ve been frequenting Southern California rinks long before the pastime rose to Instagram and TikTok fame, and they liken skating to the sensation of rollercoasters, or even flight: exhilarating, addicting and entirely irreplaceable.

In its totality, L.A.’s roller-skating community spans all ages and races, but older Black roller skaters make up its foundation. The history of Black roller-skating spans the U.S. and stretches back to the eras of Jim Crow segregation and the civil rights movement when racist rink owners would designate evening sessions for Black skaters using coded themes: “MLK Night,” “Soul Night,” and so on.

Today, many rinks use variations of the “adults only” theme to signal a welcoming space, not just for older skaters, but for the Black community and other skaters of color.

“I find it amusing, people saying, ‘Skating is coming back.’ It’s funny, it never left,” says Gregg Dandridge, a professional stuntman and martial artist who first began roller-skating in the ’70s. “We’re not saying that skating was invented by people of color. However, it never died with us. It was always a sense of family. There’s people skating who are my grandparents’ age.”

L.A.’s roller-skating scene — its signature small-wheeled footwork, the rise and fall of different rinks across the city — was featured in the award-winning 2019 documentary “United Skates.” If today’s roller-skating resurgence on social media centers on the aesthetic allure of the individual skater — often a young, slim, white woman whose slow-motion crossovers mimic floating on air — the roller-skating featured in “United Skates” is everything but. Twists and turns executed faster than the eye can see, complex footwork set to hip-hop and R&B, old-school slow grooves, high-speed dives and synchronous group skates reflect years of practice. It’s a multigenerational community activity, one that’s rarely reflected in the 10-second video bites that circulate TikTok and Instagram.

“Make no mistake about it, now: skating is Black and white. We just don’t have the same groove,” Owens says.

For the Black community, indoor rinks have served as essential spots for gathering with friends and family. Every week, skaters of all ages dress up for a night out, pack board games and bring home-cooked food to enjoy at the rink’s sideline tables.

“Now, this is where you come into the racial break,” Owens says. “In the white community, it pretty much died after the ’70s. But in the Black community? It’s been alive and well since even before the ’70s. The only reason the sport ends up dying is because the public is kind of fickle, things change, rinks close, and the mainstream white crowd moves on to other things.”

There are three indoor skating rinks left in the greater Los Angeles area:Northridge Skateland in the San Fernando Valley, Moonlight Rollerway in Glendale and World on Wheels in Mid-City. The first two have operated continuously since the ’50s, and World on Wheels remained open from 1981-2013, only closing due to bankruptcy and later reopening in 2017 with the financial support of rapper and L.A. icon Nipsey Hussle.

Rink closures have become an all-too-common sight, especially in major cities like L.A., where a combination of increasing property taxes, landlords unwilling to renew leases and tension between white rink owners and Black skaters can stack the odds against the rinks’ survival.

Tammy Franklin, a 57-year-old nurse who retired just after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, can trace the chronology of her past L.A. haunts with precision. At 12 years old, she frequented a rink on Rosecrans Avenue in Gardena. One by one, as rinks would close, she and her friends would gravitate to another: Flipper’s Roller Boogie Palace, Sherman Square Roller Rink, World on Wheels, Skate Depot. Now, she’s at Northridge Skateland.

“There’s nothing like the feeling of being on your wheels and going with the music, just being in your own world,” Franklin says. “It’s like, people go to a nightclub to dance, and you have to wait for somebody to dance with you. Well, with skating, you don’t have to do that. You’re in your own world, you can listen to the music and just do your own thing. And everybody has their own moves, everybody has their own special something. Not being able to skate regularly now has really, really upset me.”

As the coronavirus pandemic drags on and the length of California’s business closures remains unclear, roller skating’s most devoted base is now entering their seventh straight month of having zero access to indoor rinks.

“It’s been the most stifling thing,” Dandridge says. “Imagine you’re a marathon runner. And you love running. And all of a sudden, somebody breaks both your legs. ‘But you’ll be alright for six months, don’t worry about it. You just sit and watch TV.’ Would that make you feel any better, or would you feel worse? It’s that. It’s like a part of my psyche just closed down. That outlet for bad energy, bad vibrations, is gone.”

To the average person who only visits a skating rink for birthdays or outings with friends, the hardships roller skaters and rink owners face can feel far removed. But visit Northridge Skateland any Sunday night, General Manager Courtney Bourdas Henn says, and you’ll find hundreds of regular adult skaters, some of whom have taught their great-grandchildren how to skate. At a typical “21+ Grown Folks Roll” night, about 300-400 people show up. Moonlight Rollerway sees similar numbers for its Monday night “18+ Adult Sessions.”

“We have a massive adult population of skaters,” Bourdas Henn says. “Massive. And for many of them, their only real form of physical activity is skating. And skating outdoors can pose challenges for many people: the ground is uneven, it’s dirty, there’s rocks, there’s all sorts of slip and trip hazards. So I know especially for my adult skaters who are in their 60s and 70s — of which I have hundreds who come each and every week — the prospect of them skating outside, especially in the extreme heat, poses real challenges.”

Bourdas Henn has worked at Northridge Skateland for 35 years. Her first job, at 16 years old, was working as its snack bar attendant. The rink shut down on March 15, when the coronavirus first hit the U.S. and has remained closed ever since.

“We’ve had virtually no sales for five months,” Bourdas Henn says. “To add insult to injury, in addition to no income, we had to refund a ton of money to guests who booked events. Not only are we not making any money, we’re paying out money.”

Any funding received through the federal government’s emergency Paycheck Protection Program loan is all but exhausted, Bourdas Henn says, which forced her to lay off her entire part-time team until the rink can reopen.

At Moonlight Rollerway, owner Dominic Cangelosi and Office Manager Adrienne Van Houten face a nearly identical situation. Since closing on March 16, Van Houten says their rink has made virtually zero income. Despite a PPP loan temporarily supporting part-time staff at the start of the pandemic, only four people currently remain on the payroll. Van Houten takes individual appointments for purchases and repairs at the rink’s shop, staggered throughout the day so that only one person enters at a time.

Roller-skating’s resurgence on social media has boosted sales of outdoor skates and wheels at Northridge Skateland and Moonlight Rollerway, but only in a limited way. Extraordinarily high demand and temporary factory shutdowns have created a nationwide skate shortage, preventing local rinks from quickly restocking their inventory.

For Van Houten, one of the biggest challenges is the uncertainty surrounding the future of skating rinks. Roller rinks fall under California’s “family entertainment center” businesses category, which has its own specialized reopening protocols released by the state’s public health department. A COVID-19 guidance document released on July 29 detailed reopening procedures for other family entertainment centers — bowling alleys, arcades, movie theaters — but explicitly omitted roller rinks and ice rinks. The document cited three reasons for the exception: an inability to maintain social distancing, a large number of guests gathering from different households, and the fact that a central part of the activity involved physically circulating within a space.

This prompted a roller rink owner in Citrus Heights to start a Change.org petition asking Governor Gavin Newsom to allow rinks to reopen. At Moonlight Rollerway and Northridge Skateland, staff have installed protective plexiglass barriers and hand-sanitizing stations, preparing revised protocols for the day they will be allowed to resume business.

“My skaters are desperate to come back to the rink,” Bourdas Henn says. “I get text messages and phone calls every week from multiple people. ‘Will you please just let me come out? I won’t tell anybody. Can 10 people come at a time? We’ll pay whatever you want us to pay.’”

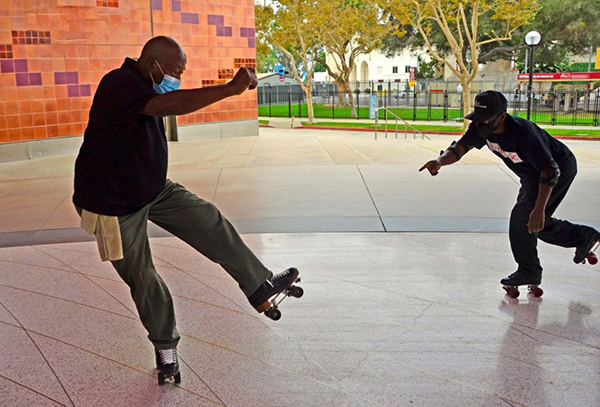

Some skaters have successfully made the transition outdoors, meeting up to skate at basketball courts and parking lots, or sharing space with bicyclists on the L.A. River walkway. Franklin, who has been skating alongside her best friends for over 40 years, says at first, they were able to host socially-distant family picnics and skate sessions with their grandchildren at nearby parks. But as more skaters discover hidden gems, crowds grow far beyond capacity, and parks and recreation staff have to revoke their permission to skate.

“It’s been very stressful because I didn’t have a way to release, you know what I mean?” Franklin says. “Skating is a release. It’s an energy, it’s a movement, that nothing compares to.”

Liz Fillmore, a social worker who celebrated her 50th birthday at Moonlight Rollerway, likens the community she found through roller-skating to church — a place where you can fill up, spiritually, by being with your people and feeling a sense of freedom. One of her proudest memories was skating 22 miles along the Los Angeles Marathon route shortly after undergoing surgery for a new heart valve.

“They were like, ‘Do you have any questions?’ And I was like, ‘When can I skate?’” Fillmore says. “And they were like, ‘Um, let’s get off the blood thinners, OK?’”

For Kelly Tomlin, who has been skating at Northridge Skateland since she was 7 years old, picking skating back up later in life is what brought her back to her identity.

“I always said after I had my son, I was going to go back to skating, but I never did,” Tomlin says. “And then once they went off to college, I was completely lost. The second I put my skates back on, I just felt like my old self again. It’s kind of like, you feel who you are when you’re skating.”

Marianne Notter, who is 57 years old, has been skating every week for nearly 40 years. She started as a street skater, then moved to L.A. in 1984 and skated at Venice Beach before transitioning to rinks. She says her friends all say they’re never going to take skating for granted again.

“It’s hard to describe when you’re not in it,” Notter says. “When you get ready to go to the rink, it’s almost like a kid going to Disneyland. We’re like big old kids on those eight wheels. I always say, ‘I’m going to die in my skates. Bury me with my skates.’”

For now, skaters make do with outdoor wheels and the smoothest cement they can find. Owens calls it a decentralized, floating rink, as skaters will call or text each other to arrange meet-ups in different corners of L.A. every day of the week. For many of them, being outdoors simply isn’t the same — the freedom of speed, rhythm and synchronized group skating is stripped away — but it’s better than no skating at all.

“You know what our expression is? ‘Skaters gonna skate.’ So we skate wherever we can,” Owens says. “And if they kick us out? We find another spot. Ad nauseam.”