Opinion: Los Angeles Is Much Safer Than It Used To Be. Really?

Perhaps selling yourself on how safe Los Angeles is today based on statistics and rhetoric can be easier to do when recalling the early 1990s of gangs, crack cocaine, the police beating of Rodney King, the 1992 riots, and the murders of Nicole Simpson and Ron Goldman.

By JIM NEWTON

CAL MATTERS

It’s hard to generalize about a city like Los Angeles, and even harder to do so about Los Angeles County. What could 10 million people, who speak scores of languages, hail from every corner of the earth, cover the range of affluence from some of the world’s richest to many of the nation’s desperately poor, share in terms of politics or public concerns?

And yet generalizing is the business of politics, and whether there is a consensus view of safety in this region is at the heart of the race for district attorney.

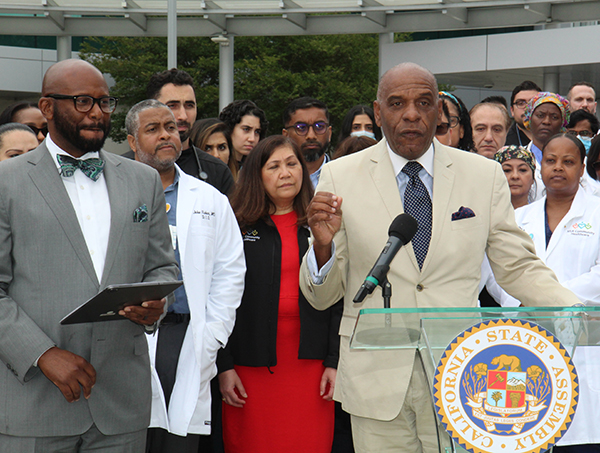

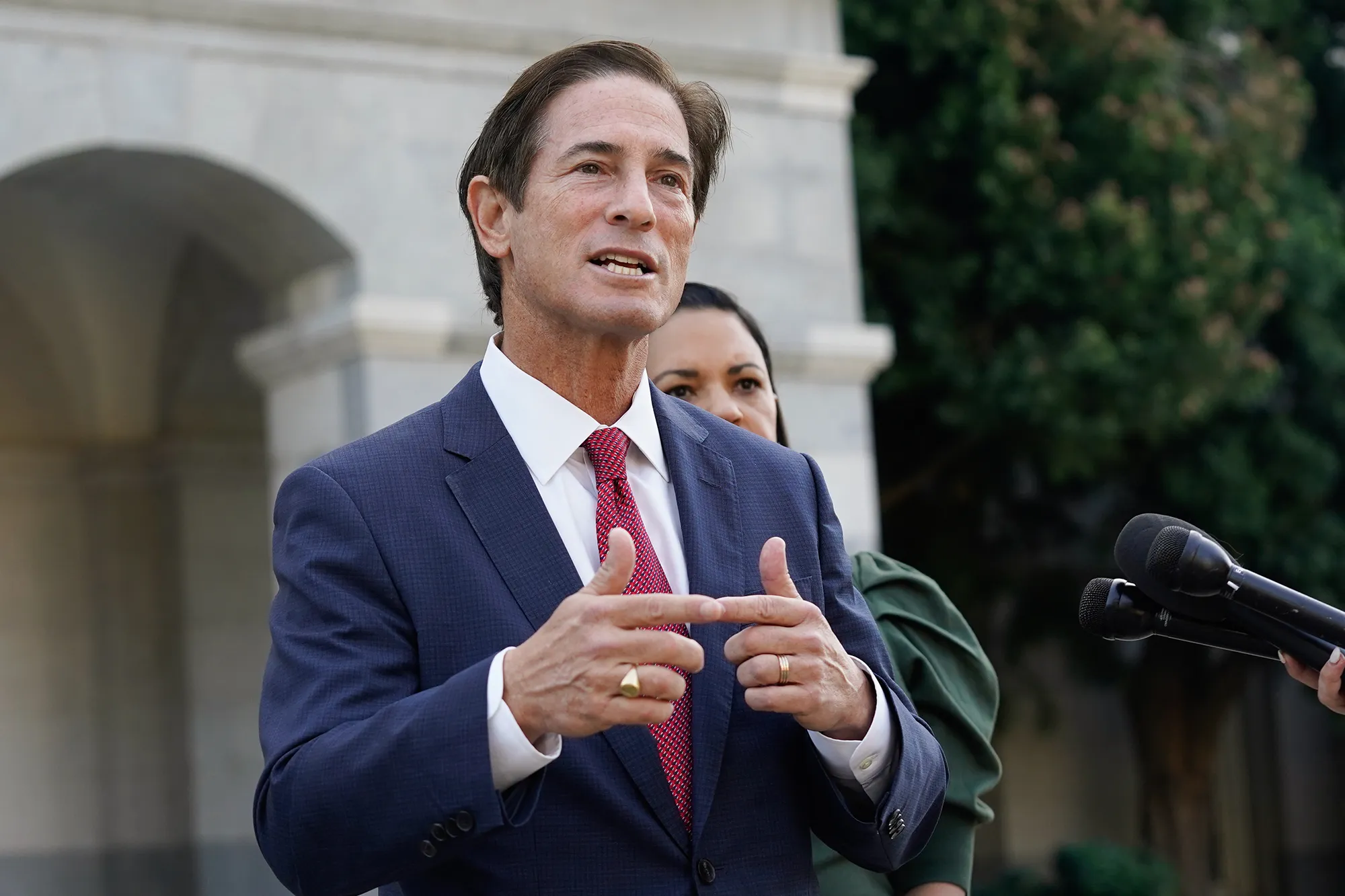

Incumbent George Gascón argues that community safety is his top priority and that he is making Los Angeles County safer. Challenger Nathan Hochman claims Gascón has presided over a “massive increase” in property crime as well as dangerous spikes in violent crime.

The November election, Hochman told me recently, is going to turn on the question of “Who is going to keep us safe?”

Those competing claims reflect selective use of data — by both candidates — as well as assumptions about the role of prosecutors and the views of this gigantic, diverse county.

First, the assumptions: Both Gascón and Hochman, by focusing on crime, accept the idea that the actions of prosecutors are strongly related to incidents of crime.

That’s not a crazy assumption, but it’s hardly undisputed. There are studies that question the role of the death penalty in deterring crime, for instance, and many observers have noted that American states with the death penalty generally have higher rates of violent crime than those without it. (Gascón opposes the death penalty; Hochman supports it)

It’s possible that other decisions by prosecutorial offices — which charges to pursue, how to deploy resources for competing priorities — can affect lower-level offenses. But it’s glib to argue that simply swapping out the district attorney will dramatically affect crime rates.

A better argument can be made that policing strategies have that effect. Neither Gascón nor Hochman is particularly concerned with those.

As for the larger question, is crime skyrocketing in Los Angeles, and is it Gascón’s fault? Short answers: no and no.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office reported 13,743 violent crimes in Los Angeles in 2021, Gascón’s first year in office. That number jumped in year two and fell in year three, when the department reported 15,472 violent crimes, a three-year increase of about 12%. The department reported nearly 53,000 property crimes for 2021 and more than 60,000 last year, an increase of 15%.

It’s nothing to be proud of, but it’s hardly a crisis, and it took place during a pandemic and under the leadership of the county’s unhinged sheriff, Alex Villanueva.

Moreover, homicides have fallen during the same period, robberies and aggravated assaults have held relatively steady, and larcenies, car thefts and arson are at about the same level. Burglaries did take a big jump right after Gascón took office, but they have since leveled off.

Note, too, that those are data from the Sheriff’s Department. The LAPD patrols the city of Los Angeles, by far the biggest in LA County, and its cases fall under Gascón’s jurisdiction, as well.

Homicides in the city were down from 392 in 2022 to 327 last year, part of a broader decline in violent crimes. Property crime is down since 2021, though some thefts have risen in those years.

Those, too, are on Gascón’s watch.

Again, nothing to brag about, but such a far cry from this community’s genuinely dangerous eras that it is simply untrue to claim, as Hochman does, that Los Angeles is in a criminal spiral. Hochman contends that the data do not fully capture crime, especially property crime committed against store owners who have lost confidence in police and prosecutors to address their concerns.

Real property crime, he says, “is going through the roof.”

Still, there’s reason to believe that he’s misreading the public or exaggerating the effect of all of this. Just last month, UCLA released its annual quality-of-life index, which measures the public’s level of satisfaction or discontent and identifies the issues driving those feelings.

This year, the survey’s dominant finding was that residents of the county are most concerned about the cost of living, which shaped an all-time low index score and the area of life with which they had the most complaints.

By contrast, residents were mildly positive about public safety and quite happy with their neighborhoods.

Hochman again questions those findings, arguing that his conversations with voters and residents reveal deep levels of anxiety and that some issues are masquerading that.

For instance, concern about homelessness, he said, is often more concretely a fear of crime — of being victimized by unhoused people so overcome by mental illness or addiction that they are erratic and dangerous.

If true, that could mean that a survey suggesting that homelessness is a top concern for Los Angeles voters is improperly measuring it as a humanitarian response rather than something more basic: a fear of crime.

Fair enough, but anecdotal data works both ways. Those I talk to about Los Angeles issues almost always start with homelessness. In some cases, yes, they express annoyance with homeless people — cars getting broken into, walkways that feel unsafe — but overwhelmingly what I hear are expressions of sadness and empathy, mixed in with considerable dismay that the government is not doing more to protect those who are suffering so mightily.

In my conversations, unease about homelessness is followed closely by complaints about traffic and the cost of living.

That was not always the case. In the early 1990s, every conversation I can recall when it came to civic life in Los Angeles was connected to crime — to gangs, crack cocaine, the police beating of Rodney King, the 1992 riots, the murders of Nicole Simpson and Ron Goldman.

It was an endless parade of violence — more than 1,000 people a year were murdered in Los Angeles those days. Crime and the fear of crime united the county, stretching from South Central to Beverly Hills, and was unmistakably the center of civic life. It’s what got controversial police chief Daryl Gates bounced from the Los Angeles Police Department and elected Richard Riordan on a promise that he was “tough enough to turn LA around.”

That’s when it was actually possible to generalize about Los Angeles County, to argue that it spoke with a single voice on the issue of crime. That’s not true today.

Jim Newton is a veteran journalist, best-selling author and teacher. He worked at the Los Angeles Times for 25 years as a reporter, editor, bureau chief and columnist, covering government and politics. He teaches at UCLA and founded Blueprint magazine.

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics. Published with permission of CalMatters recall me