Reliability, equity and the road ahead for Scattergood

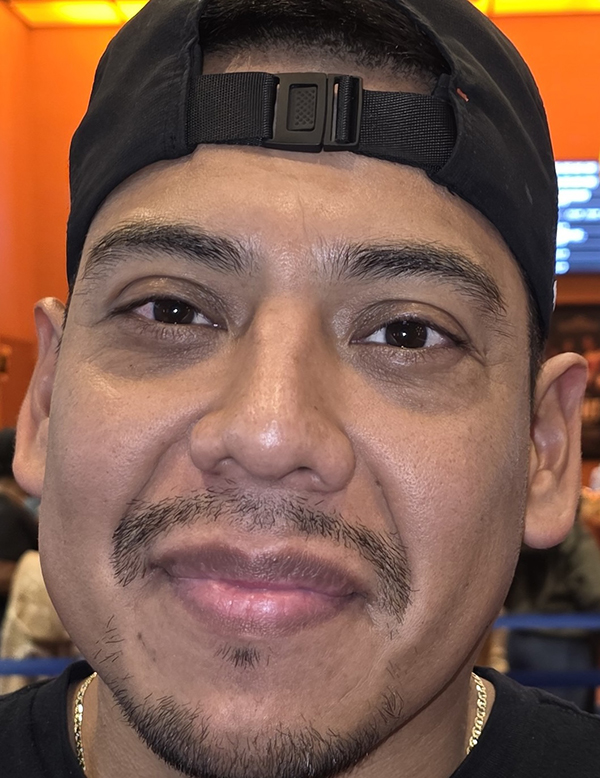

William Funderburk

By William W. Funderburk Jr.

Guest Columnist

On Oct. 28, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Board of Commissioners voted to certify the final environmental impact report for the Scattergood Modernization Project. More than 60 Angelenos — including longtime environmental justice warrior and mother of late DWP manager Cindy Montañez Margarita Montañez — testified at the hearing, raising questions about reliability, equity and long-term planning posture.

Located in West Los Angeles, Scattergood is one of four natural gas-fired power plants in Los Angeles. It can be started up and turned off on close to a moment’s notice, providing the DWP with reliability and balancing power when intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind fluctuate.

The DWP argues that replacing aging turbines is essential to maintain grid stability. The proposed hydrocarbon-ready turbines would provide 300 to 400 megawatts of firm capacity — capacity that cannot be replicated with solar and batteries alone, given land constraints in El Segundo and surrounding areas.

Reliability, however, is not just a technical term. It touches public health, union jobs, training and long-term investment in public works. It also intersects with equity — who benefits, who bears the burden and how decisions are interpreted across communities.

In 2016, the DWP adopted the Equity Metrics Data Initiative. The framework committed the utility to track 15 equity metrics across infrastructure investment, customer programs, service reliability and workforce representation. In 2018, the DWP board adopted 35 additional metrics. Those metrics were designed to inform planning and procurement, to promote efficiency through transparency and to ensure that equity was not just cited — but measured.

While the equity initiative was referenced in prior planning efforts, its metrics did not appear in the Scattergood environmental impact report. This raises important questions about how equity frameworks are integrated into infrastructure decisions and how communities interpret long-term planning posture. The absence of these metrics in the public-facing documents underscores the need for continued dialogue and transparency.

Environmental justice advocates have also raised concerns about hydrogen. While the DWP frames hydrogen as a renewable solution, much of it is derived from methane, a fossil fuel. The Environmental Protection Agency concluded there was “no statistically significant difference” in emissions data, but that finding has been challenged by groups like the Environmental Integrity Project. Without clear public data, the promise of hydrogen remains speculative.

The Climate Registry, which has helped lead regional and global efforts in climate accounting and policy, offers a model for transparency. Its subnational framework encourages cities and utilities to disclose emissions, equity metrics and climate commitments in a standardized format. The DWP could benefit from deeper alignment with these protocols — not just for optics, but for operational clarity.

Ultimately, Scattergood is not just a plant — it’s a symbol. Of what Los Angeles is willing to confront, and what it’s still learning to integrate. The vote may be final, but the conversation is not.

Equity must be threaded into every California Environmental Quality Act document, procurement plan and resource roadmap. Community media must be funded to interpret these decisions. And metrics must match the mission.

Attorney William W. Funderburk Jr. is a senior advisor and board member of the PermaCity Foundation. He also is a former DWP board member, and author of the upcoming book, “Mapping Water and Power.” He will speak next week in Brazil at the United Nations climate conference.

LIFTOUT

While the DWP frames hydrogen as a renewable solution, much of it is derived from methane, a fossil fuel.