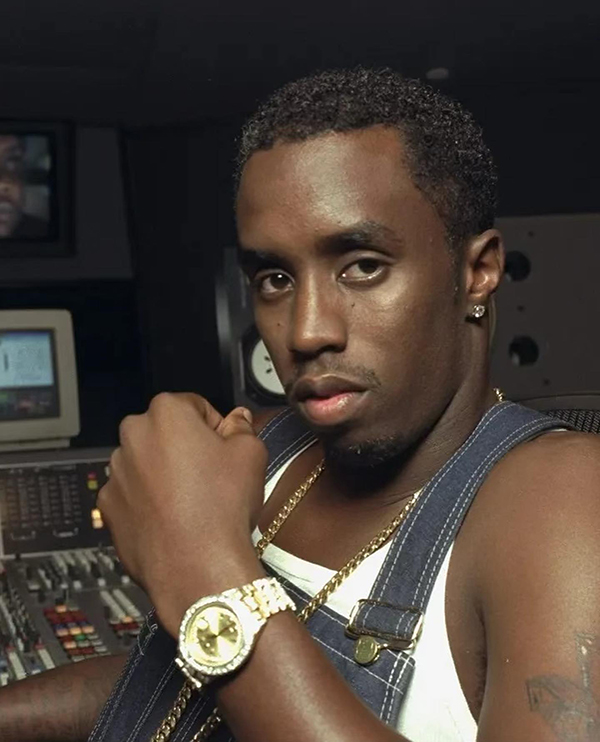

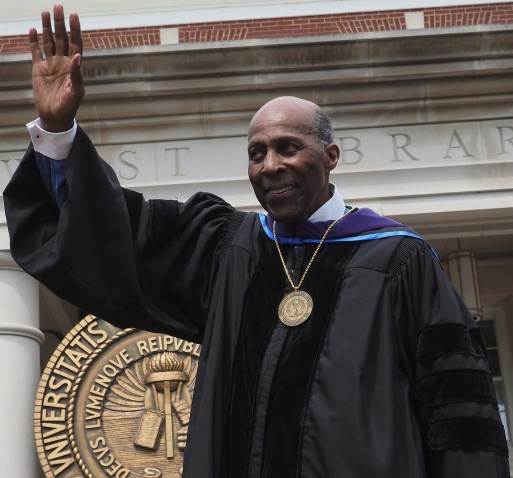

Victim’s family celebrates passage of Wakiesha’s Law

Assemblyman Isaac Bryan speaks alongside Wakiesha Wilson’s family and community advocates during a news conference Dec. 11, outside the Los Angeles Police Department’s Metropolitan Detention Center. The event marked the passage of Wakiesha’s Law, which requires families to be notified within 24 hours if a loved one is hospitalized or dies in custody.

Photo by Stephen Oduntan

By Stephen Oduntan

Contributing Writer

LOS ANGELES — For four days, Lisa Hines searched for answers about her daughter.

She went from jail to jail, hospital to hospital, trying to find out what had happened to Wakiesha Wilson, who was arrested during a mental health crisis in 2016. No one called her. No one explained why her daughter never came home.

Nearly a decade later, California has passed a law in Wakiesha’s name — ensuring that no family has to endure that silence again.

Known as Wakiesha’s Law, the new statute requires county, city and municipal jails to notify families within 24 hours if a loved one is hospitalized for a serious medical condition or dies while in custody. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the bill into law in September, and it took effect immediately.

“When I found out my baby had died, those were the four longest days of my life,” Hines said Dec. 11, at a press conference outside the Los Angeles Metropolitan Detention Center. “Because of Wakiesha’s Law, I can now say no one will have to go through that again.”

Wakiesha Wilson died in an LAPD holding cell in 2016. The Los Angeles County Medical Examiner later ruled her death a suicide — a conclusion her family has long disputed, saying she showed no signs of suicidal intent and was looking forward to returning home.

What the family does not dispute is what came next: days without notification.

“No one in the city called her. No one in the county called her,” said Assemblyman Isaac Bryan, D–Culver City, who authored Assembly Bill 1269, which became Wakiesha’s Law. “The coroner didn’t call her. The judge didn’t notify her. The city attorney, the district attorney — nobody notified the family.”

Instead, Wilson’s relatives arrived at court for her next scheduled appearance, only to be told she had failed to appear — without explanation.

“They had to do the hard work themselves to understand what had happened,” Bryan said.

For Sheila Hines, Wakiesha’s aunt, the memory of those days remains vivid.

“For four days we were riding — hospitals, jails, everywhere,” Sheila Hines said. “Until finally someone told my sister, ‘Just call this number.’ She called — and it was the coroner’s office.”

She said the family was devastated — not only by Wakiesha’s death, but by the lack of dignity and transparency that followed.

“That should never happen to another family,” she said.

Wakiesha’s Law includes an urgency clause, meaning it became law the moment it was signed. Unlike most legislation, it did not wait until the following year to take effect.

Under the law, families now have legal recourse if they are not notified within the required 24-hour window.

Bryan said the bill passed with overwhelming support because lawmakers could not ignore the family’s testimony.

“When they came to Sacramento and told this story, it made it impossible for anyone with a conscience to vote against it,” he said.

Los Angeles City Councilwoman Ysabel Jurado, who represents much of downtown Los Angeles, said Wakiesha’s Law reflects a reality many families already know too well.

“In downtown and among the vulnerable populations I represent, we’ve seen families torn apart — spouses, parents, children not knowing where their loved ones are,” Jurado said. “Are they safe? Are they still in Los Angeles? Are they still alive?”

For advocates, the law is both a milestone and a reminder of how much work remains.

“What happened to Wakiesha Wilson should have never happened,” said Sheila Bates, a policy advocate with Black Lives Matter California. “But what should have happened afterward was that her family was notified within 24 hours — and that’s what this law now requires.”

Melina Abdullah, co-founder of Black Lives Matter–Los Angeles, noted that Wakiesha’s Law is the first California law named in honor of a Black woman.

“We cannot get justice for Wakiesha,” Abdullah said. “Justice would mean she is still here. But we can demand justice in her name — and for the benefit of all of us.”

Advocates say similar legislation is being pursued at the federal level, but for now, Wakiesha’s Law stands as a hard-won victory — forged through grief, persistence, and community pressure.

As speakers closed the event, the crowd spoke Wakiesha’s name aloud — not as a slogan, but as a promise.

Stephen Oduntan is a freelance writer for Wave Newspapers.