‘Keep our history alive’

A full century later, scholars still hope Black History Month retains its relavancy

By Janice Hayes Kyser

Contributing Writer

As the celebration of Black history turns 100 this year, historians and scholars say this is a good time to consider how to ensure the celebration of Black history remains relevant to future generations.

What has become Black History Month started as National Negro Week during the second week of February in 1926. Black educator Carter G. Woodson chose that week because it coincided with the birthdays of two individuals Woodson felt were integral to African-American freedom — Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

Fifty years later, President Gerald Ford declared February as Black History Month and it has been celebrated throughout February for the last 50 years.

One century in, there are plenty of ideas out there on how to celebrate Black history and the people who have made it and continue to make it.

“What we need is a balance of the stories we know about Black history icons such as Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King Jr. combined with more contemporary stories,” said M. Keith Claybrook, associate professor of Africana studies at Cal State Long Beach. “We have to find innovative ways to keep our history alive.

“Black history is happening every day, and we have to achieve a balance between the people and organizations from 100, 50 and 20 years ago with those from 15 and 10 years ago up to today.”

Karsonya “Kaye” Whitehead, president of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History founded by Woodson in 1915 to preserve, promote and protect Black history, concurs.

“As we celebrate 100 years of Black history commemorations I think about what American writer and social critic James Baldwin said: ‘History is not the past. History is the present,’” said Whitehead, who also is a professor of communication and African and African American studies at Loyola University Maryland.

“Part of the work we do is not just rooted in the historical past but rooted in this moment,” Whitehead added. “Slavery, the civil rights movement and other milestones in our history may feel like a long time ago, but they aren’t. It’s that continuum that helps us understand the moment we are in, how we got here, the fact we have been here before and how we can get through.”

Bringing Black history to the block, said California African American Museum (CAAM) history curator, Susan D. Anderson, is a powerful way to educate, empower and guide young people. CAAM’s Summer Nights program sets up food trucks and DJs in the museum’s parking lot to attract young people and expose them to African American history.

“It’s a cultural world and we are doing public history,” Anderson said. “It’s very gratifying to see young people come out for the food and music and then line up to go through the galleries at CAAM to learn about their history.”

In addition, Anderson believes putting a local spin on history, by telling stories of people and places that young Southern Californians can relate to is another way to take history from the pages to the people.

Los Angeles-based historian Alison Rose Jefferson agrees. Jefferson, author of “Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites During the Jim Crow Era,” has conducted surf and learn events educating Californians about the rich history of African Americans at beaches in Santa Monica and Manhattan Beach at Bruce’s Beach, once the site of a thriving Black-owned resort during the early 1900s.

“We have to approach our history in broad and creative ways,” Jefferson said, citing the murals that showcase key figures in Black history along the Crenshaw Boulevard corridor as an example of taking history to the streets.

“It’s about bringing our history to life beyond the classroom through murals, public installations, events and forums that reach people where they are and illuminate the history of that place.”

Claybrook said while the manner in which Black history is conveyed from generation to generation must evolve, the benefits of embracing history are timeless.

“History instructs us, it informs us, empowers us,” Claybrook said. “It also helps us understand what has worked and what hasn’t. Understanding the strength and resilience of our people helps us get through the dark times.”

Whitehead believes one of the most powerful ways Black people can honor Woodson and Black history is to continue to fight to protect, promote and preserve it.

“This is a very critical moment for us to understand we are up against another barrier trying to impede our progress and our people,” she said. “We are doing this work with the long arm and long eye of history not solely for the generations that are here but for the generations to come.”

Jefferson puts it this way.

“Our history is American history. There would be no history without us,” Jefferson said. “This country was built by our ancestors. We are all responsible for our history, not just the historians and scholars. We have to demand that our history is recognized. We have to keep making the case as an ongoing exercise. It’s not something that is ever going to be a given.”

Although familiar icons such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks are often touted during Black History Month, the intention is also to spotlight untold stories of heroism, ingenuity, resilience and brilliance as a means of building cultural competency, learning from the past and inspiring a new generation of Black leaders.

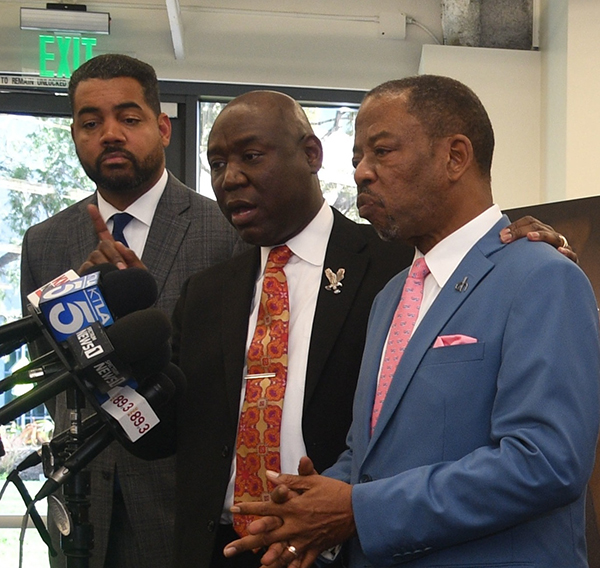

That effort, says Los Angeles-based author and activist, Earl Ofari Hutchinson, continues to this day.

“We must continue to fight to expand African-American accomplishments in books, schools and teaching in all areas of American life,” Hutchinson said.

“Carter G. Woodson recognized that this emphasis ensures that Black accomplishments must be something to take pride in and cherish, not just for Blacks alone, but for all ethnicities.”

Anthony Samad, director of the Mervyn Dymally African American Political and Economic Institute at Cal State Dominquez Hills, said the celebration of Black history is always relevant because it’s American history.

“We don’t need anybody’s permission to teach our history. It is woven into the fabric of this country,” Samad said. “If we’re teaching American history we’re teaching Black history. There’s no separating the two.”

Janice Hayes Kyser is a freelance reporter for Wave Newspapers.