‘Black August’ marks month of study, remembrance and prison history

LOS ANGELES — In Los Angeles and beyond, Black August is not a festival or holiday. Born inside California’s prison system more than four decades ago, it is a month of fasting, study and remembrance — a time to honor political prisoners, mourn those killed in the struggle for liberation and confront the systems that continue to cage and kill.

It is not, organizers stress, a celebration. Black August is solemn by design — a month of discipline and reflection, rooted in a lineage of resistance that has always come at a price.

The tradition began in the wake of the Jan. 13, 1970, killings at Soledad Prison, when three Black inmates — W.L. Nolan, Cleveland Edwards and Alvin Miller — were gunned down by guards during an interracial fight. Journalist and cultural worker Thandisizwe Chimurenga said that during the incident, guards didn’t fire warning shots.

“They aimed directly at the Black prisoners,” she said. “You could say it was a planned assassination. No guard faced accountability. It was ruled justifiable — just like when police kill us on the streets.”

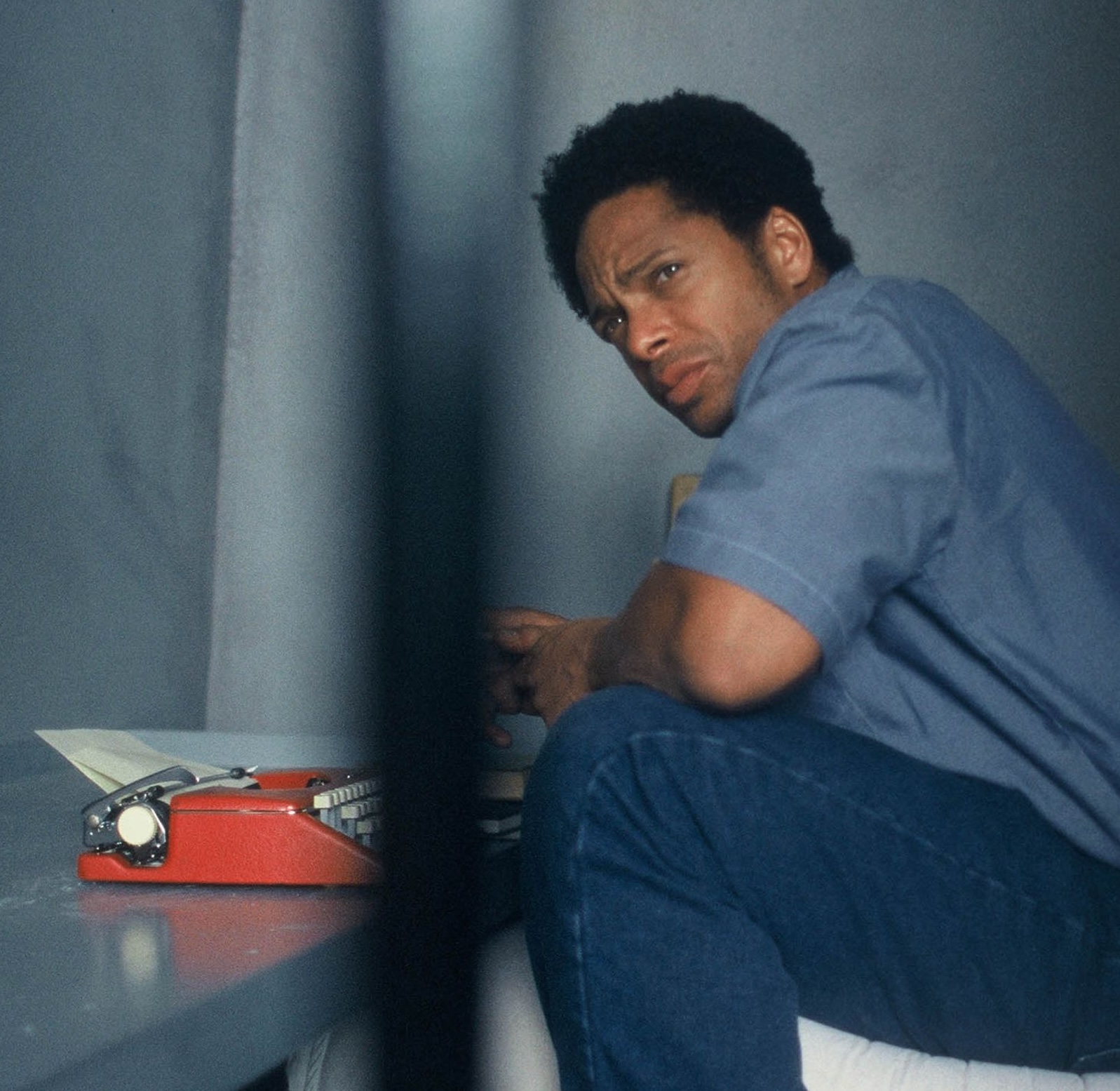

Weeks later, a guard was killed at Soledad. George Jackson and two others — the “Soledad Brothers” — were charged with murder and faced the death penalty. Their case galvanized activists statewide, linking prison conditions to the broader struggle for Black liberation.

Los Angeles quickly became a hub for that movement. Many central figures — George and Jonathan Jackson, Geronimo Pratt, Bunchy Carter, John Huggins and Sondra Pratt — had deep ties to the city. Chimurenga said imprisoned activists saw themselves as “the prison wing of the Black Power movement.”

As she described it: “When we leave prison, we are ready to join your movement — but until then, we will survive here, protect one another, call out the racism and take action against it where necessary.”

Harold Welton, now in his 60s, first read “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” as a teenager growing up in Avalon Gardens near Watts. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, he was in and out of juvenile custody and the L.A. County Jail, including what he calls a politically motivated arrest alongside other activists — experiences that shaped his commitment to the causes at the heart of Black August.

Welton helped organize a coalition that campaigned for Ruchell Cinque Magee’s release from jail in 2023, pressing the governor with letters, protests and hearings. He recalls how Jonathan Jackson’s 1970 armed takeover of a Marin County courtroom — intended to free prisoners and bring their cause to the public — ended in a deadly shootout.

Magee survived but spent more than 50 years in prison before his release in July 2023; he died months later from kidney disease — a timing that meant the state would not have to pick up the hospital bill, advocates say.

“We call that death by incarceration,” Welton said.

Welton believes young people must know this history.

“George Jackson was very principled, very knowledgeable, in the spirit of Malcolm X,” he said. “A gifted organizer, articulate and well-read — a threat to the prison system because of it.”

That threat, attorney James Simmons said, came from organized, disciplined resistance. Simmons, a member of Black August Los Angeles, said the event grew from the understanding that unorganized anger in the face of oppression often leads to destruction without change.

“People in the Black Guerrilla Family were getting murdered in prison by racist prisoners with the connivance of the administration,” he said. “They said, ‘We’re not going to die anymore.’ So they organized themselves and protected themselves.”

He added: “They wind up releasing them when they’re about to die — they don’t want the expense on their hands.”

Simmons has represented incarcerated clients and seen the power of outside advocacy.

“When I visited a client, there was a big sign: ‘No human contact. Don’t mistreat him because he has supporters outside,’” he said. “That shows the effect people can have when they speak on behalf of prisoners who can’t speak out for themselves.”

For Melina Abdullah, co-founder of Black Lives Matter–Los Angeles and BLM Grassroots, and a professor of Pan-African Studies at Cal State Los Angeles, the discipline of Black August is central. Participants follow four tenets — fast, study, train and fight. She fasts from sunrise to sundown each day in August, studies revolutionary texts like Jackson’s “Blood in My Eye” and organizes for the release of current political prisoners, including Jay Burton.

That discipline is rooted in a tradition that began in California’s prison isolation units: fasting from sunrise to sunset, abstaining from alcohol, sex and consumerism, and ending with a “People’s Feast” on Aug. 31 to honor the fallen. The practice has since spread far beyond California, observed in cities across the U.S. and internationally — from Oakland and Houston to Cuba, South Africa and Brazil — as a month, not of celebration, but of remembrance, education and resistance.

Burton was imprisoned at 16 after allegedly being framed by the Lynwood Vikings, a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department deputy gang, Abdullah said. In 36 years behind bars, he has founded three Black Lives Matter prison chapters, led hunger strikes and run reading groups — actions that have kept him incarcerated far beyond his original sentence.

“They see that as a threat, and they’ve punished him for it,” she said.

“If you talk to anybody Black, chances are they have someone they love inside the prison,” Abdullah said. “Anybody could be free this morning and be somebody who’s behind the walls tonight. And so we have to remember that the fight for prison folks is also the fight for ourselves.”

Chimurenga sees a direct line between the Soledad killings and the broader pattern of state violence against Black communities.

“Black resistance is feared in this country,” she said. “That’s the other reason it’s important for us to commemorate Black August — to remember we have always resisted, and we always will.”

Inside and outside prison walls, that resistance takes many forms: political organizing, cultural work, mutual aid, survival. “Sometimes, simply resting and finding joy in the face of those who seek your destruction is powerful resistance,” Chimurenga said.

Abdullah hopes people will carry the spirit of Black August beyond its 31 days.

“August is when we direct our energy most intentionally, but it’s not just one month,” she said. “We have to fight for our people inside every single day, and adopt abolition as a daily practice.”

Stephen Oduntan is a freelance reporter for Wave Newspapers.