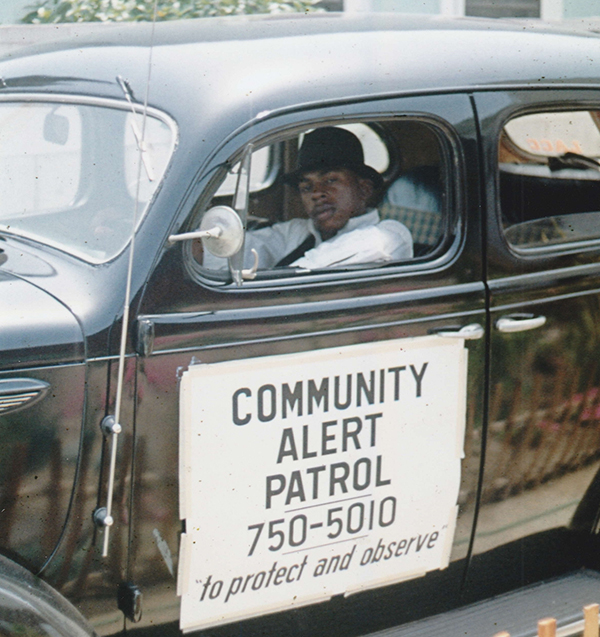

Community safety partnerships help make high-crime neighborhoods safer

By Sue Favor

Contributing Writer

SOUTH LOS ANGELES — Ellen Pace walks every morning. But for a while, the Harvard Park resident would drive to another neighborhood for her walk.

“At one point in 2014, to get my exercise in, I literally got in my car and drove to Overhill [Drive, in Windsor Hills] to do my walking,” the retired school administrator said.

These days, however, Pace and her neighbors are staying closer to home for everything. On weekday evenings and on weekends, Jackie Tatum Harvard Recreation Center Park is teeming with children on the playground, teens using the skateboard park, and adults and families on the walking track and on the sports fields.

The formerly high-crime area feels safer because of the Community Safety Partnership branch the Los Angeles Police Department opened at the park in 2017. Through steadily building relationships with community residents, a dedicated group of officers has helped to lower crime and maintain a presence that feels protective.

“We are encouraged by that crime-reduction number, though we understand we could be better and can lean toward our community partners to assist, rather than implementing enforcement,” said Capt. Ryan Whiteman, who oversees the Harvard Park Community Safety Partnership branch.

The duties of officers working the community partnership detail diverge far from making routine car patrols. A typical day at the Harvard site may involve a walking club with residents, coaching youth baseball through the city’s Recreation and Parks Department, checking in with Slauson swap meet entrepreneurs, or a group meeting with residents.

Whiteman said the ultimate goal is to empower community members through a safe environment and connecting them with resources.

“Our tenets are public safety, safe passage, parks and recreation, and working with our partners to really enhance and bring services to the area,” he said. “We want to make sure the community grows and is able to solve some of their own problems internally, without having to have the intervention of police.”

Whiteman said he begins his daily shift looking at crime statistics and then making plans for prevention and deployment, while also planning for community events. The rest of his day is spent working with the people he calls LAPD’s community partners.

“If they have suggestions or concerns about whether or not we’re doing what we’re supposed to be doing, we hear that and we make adjustments,” Whiteman said. “And to be honest, those adjustments are a daily thing. If there are things we do today at any site that draw questions from our community partners we look at them and may make adjustments. Then we measure our daily effectiveness.”

One example of how the Community Safety Partnership model works in Harvard Park, and the other nine partnership areas around South L.A., is in how police handle gatherings. Whiteman said he and his officers like to aid residents in hosting those events out of cultural sensitivity and historical awareness.

“We facilitate [gatherings] with ground rules and work with community leaders, who act as intermediaries to the community,” he said.

Ground rules usually include a no-alcohol and drug use policy, and a general length of time of the event.

“If things are a little off base, we’d rather have a community member say ‘OK, this is what we agreed to, and these rules agreed to aren’t being followed,’” Whiteman said. “It’s better to ask, ‘could you go talk to that person and get them back on track?’ Then the situation is handled without the police going in and stirring the hornet’s nest, so to speak.”

Whiteman said crime is down almost 6% in the area from last year. He attributes the success of the program to its emphasis on relationships.

“The biggest thing for us is working with our community partners, and making sure the community engagement tenet is something we keep in mind in every daily activity and every direction we give our officers,” he said. “We don’t want to inhibit relationship-building with over-deployment of officers, where the community feels like there’s too much enforcement.”

The Community Safety Partnership program was the brainchild of LAPD Capt. Emada Tingirides, who became the Community Safety Partnership Bureau’s first chief 13 months ago, when the branch was created, and civil rights lawyer Connie Rice.

Tingirides was a sergeant at the Southeast Division when she was selected by former LAPD Chief Charlie Beck in 2010 to put the program together with Rice. Rice had been working in gang intervention and had a vision of a trust-based police program in Watts. Tingirides had seen homicide, violence and gang “taxation” of residents in the area’s three housing projects and had similar thoughts.

The concept was based on putting a group of dedicated officers in the city’s most vulnerable communities, who would work more as partners than enforcers. The city hired the Urban Peace Institute to conduct surveys.

They asked residents what they didn’t like about the police, what they’d like to see from police, and what resources were needed in the area. Tingirides, Rice and Beck developed the framework for the Community Safety Partnership program from the data.

The first sites were set up in the Jordan Downs, Nickerson Gardens and Imperial Courts housing projects in Watts, as well as Ramona Gardens in East Los Angeles. The Harvard Park Community Safety Partnership site, established in 2017, is the first that isn’t located in a housing project. Precipitating its selection was a large crime spike that began more than a decade ago.

Among the more frightening incidents to residents was the September 2012 shooting and killing of a young man sitting at a picnic table at Harvard Park, and a July 4, 2016 drive-by shooting that killed a man just down the street. Following the “traumatizing” events, City Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson introduced a motion for a Community Safety Partnership site in the area, and it was approved.

After another Urban Peace Institute survey, and countless community meetings, the program was launched the next year.

“CSP areas are selected based on the amount of violence and the need,” Tingirides said. “Not every division within LAPD needs a CSP site. These areas are selected because they are some of the most vulnerable, whether that means being in a food desert, having a lack of resources or having a lot of trauma.”

“We are very specific in selecting areas, and we wanted to make sure they were areas where residents didn’t necessarily like the police.”

Each site has 10 officers and a sergeant who make a five-year commitment to the assignment. Unless there is an extreme emergency, officers stay in the area daily. The system is designed to allow residents to get used to seeing the same people, which builds trust. That strategy has been very effective.

Longtime Harvard Park resident Kimberly Barrio said that before the establishment of the Community Safety Partnership site there, shootings and robberies were commonplace. Now when she and her family see police officers, it’s for the good.

“They make me feel safe around the area, that I can take the kids out and play,” Barrio said. “They’re always passing around, checking on us or our neighbors. They ask us how we’re doing, and let us know they’re there.”

Barrio said it took her a while to get used to seeing police officers and not automatically assuming there was something wrong. But she finds the proof of their work in her kids.

“One of the things I have in my heart is that my son is 4 years old now, and he wants to be a police officer,” she said. “They have taken the time to say hi to the kids. They play soccer with them.”

Whiteman said making residents feel safer is the goal.

“It’s less about how many people we can arrest and how many tickets we write, and it’s more about how many relationships we have built and how we’ve made that community feel about public safety,” he said.

“Law enforcement is driven by data. We can see a 20% reduction in crime, but if we talk to these kids and their parents and ask them if they feel safe walking to the store at 7 p.m. and they say no, then public safety hasn’t been met. Because the mental part of being safe isn’t reconciled by numbers.”

“Sometimes it’s uncomfortable,” he said. “Sometimes people feel like different sides of the partnerships may not have hit the mark, so we have some conversations that are not comfortable, which is good because there’s growth. And everyone’s trying to build a bigger capacity to understand where everyone else is coming from.”

Ultimately, Whiteman tries to strike a balance.

“The key to be aware of is with this partnership everyone has a little bit of a different interest. And keeping those interests aligned and equally served is probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” he said.

But it is an effort that means a lot to residents.

Pace is involved in the partnership, as is longtime resident Arthur Franklin, a former gang member.

“I absolutely advocate what these officers are doing, and I’m trying to be one of their driving forces to help them,” Franklin said. “There is more education, more awareness these days. Citizens are more willing to step out and give officers a chance.”

Tingirides said there have been detractors to the program, including those who call it “women’s policing.” But overall, the response has been good, and other police agencies from around the country have contacted her with questions.

Though it is a bigger investment of resources, Tingirides said the Community Safety Partnership is ultimately worth it.

“Infusing this public health, wrap-around approach and understanding the culture is a deep dive,” she said. “But if we can get rid of the root causes of issues, the CSP can ultimately go away, because we built the culture and connected the resources so the community can survive on its own.”

Sue Favor is a freelance reporter for Wave Newspapers, who covers South Los Angeles. She can be reached at newsroom@wavepublication.com.