Disabled struggle to find accessible housing after fires

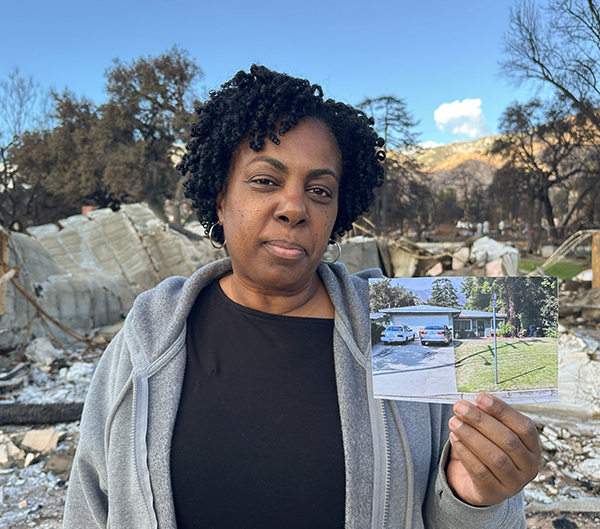

Residential facility administrator Retha De Johnette holds a photo of an Altadena assisted living home that was destroyed by wildfire in January. Behind her are the remains of the building.

Photo by Daniella Lake

By Daniella Luke

Contributing Writer

ALTADENA — When wildfire tore through this community last January, Retha De Johnette never expected the disabled residents of the assisted-living facility she runs to remain displaced across the Southland nearly a year later.

“They’re spread out all over, in all kinds of random places right now, and it’s pretty devastating,” she said.

After disasters — natural or otherwise — people with disabilities often find themselves in temporary lodging that offers a roof, but lacks the safe, customized environment they need. This can result in many dangers and difficulties, including leaving people in wheelchairs or who require walkers to spend weeks or months in unfamiliar rental housing with dangerous stairways, rather than accessibility-friendly ramps.

Also, “temporary” doesn’t mean they will ever get back their old life; people with disabilities are up to four times more likely to never return home after a natural disaster, according to 2024 U.S. Census Bureau data.

Still, they might feel relatively lucky given that people with one or more disabilities — a group that includes more than 70 million Americans — are also four times more likely to be critically injured or die in a natural disaster than other people, according to the Washington, D.C.-based National Council on Disability.

In Altadena, Anthony Mitchell Sr., a father with a prosthetic leg who used a wheelchair, and his son Justin Mitchell, who suffered from cerebral palsy, called 911 the second day of the Eaton fire, according to records obtained by LAist. Mitchell Sr. told the dispatcher that he was terrified as sparks flickered in his backyard.

Eleven minutes later, he called again to say he could see flames and he begged emergency responders to “hurry please” because both he and his son were disabled. A few minutes later, a relative who wasn’t at the residence also called 911, desperately telling the dispatcher, “They can’t get out of the house.”

Dispatchers replied that help would arrive as soon as possible. By the time it did, Anthony and Justin were dead.

Their tragedy was similar to many others. Amid the chaotic evacuations from Altadena and Pacific Palisades during the fires, 31 lives were lost. At least 24 of them were over the age of 65, had disabilities or both.

De Johnette, the administrator of an assisted-living organization named Robinson’s Manor — up the street from the Mitchells’ destroyed home — believes the evacuation order came too late. “I think that was a big problem, especially for people who need special assistance,” she said.

Robinson’s Manor, founded by De Johnette’s parents Laura and Reginald Robinson 36 years ago, housed four men and six women in a pair of homes in Altadena.

Laura is a 75-year-old woman from Colombia who moved to Los Angeles in the 1960s, obtained a job at a nursing home in Altadena and then cared for children with disabilities. She and her husband later opened their eponymous Manor, which has housed some of its residents for two decades.

Such facilities often aim to be safe, accessible and comfortable spaces for people who are elderly, live with disabilities or both — and who, during emergencies, tend to require special assistance and more time to evacuate.

West Altadena, where Robinson’s Manor is located, received an evacuation order nine hours after the fire broke out. The area was home to nearly all of the Eaton fire fatalities — 19 in all, including Anthony Mitchell Sr. and his son.

An after action review, released in September by McChrystal Group, cited residents who said they never received any evacuation notice. This may have been due to “a public safety power shutoff, downed power lines, or cell towers being impacted by the wind, fire, or smoke,” according to the report, which was commissioned by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

The women’s home at Robinson’s Manor was spared by the flames, and the six female residents returned home weeks later, after smoke-related safety concerns were resolved. But the men’s home was reduced to rubble, leaving little more than caved-in walls and a scorched file cabinet.

During the months that followed, the four male residents — including two in their 70s — were briefly lodged in various hotels and Airbnbs. At the time, De Johnette emphasized their need for stability.

“They’re tired of being moved around,” she said. “They want to be home in a place that they know.”

At one of the Airbnbs, Laura, who is in her mid-70s, was helping to get the men settled when she slipped on a step-down between two rooms, fell and banged her head on the ground.

Beyond the initial concern for her mother, De Johnette thought of the displaced Robinson’s Manor residents, whose conditions include vision loss, schizophrenia, autism and seizure disorders.

“Oh my gosh,” she said, “it could have been one of them.”

The scare led De Johnette to seek a different solution for the displaced residents. She sought permission to move the men into the women’s home, which had four open beds, familiar faces and a safe environment.

But the California Department of Social Services denied that request, citing capacity limits, even before sending any inspectors to look at the space, De Johnette said. In the aftermath of fires and amid a larger housing shortage in Los Angeles County, she found the decision and the process perplexing.

“I just feel like the response has not been person-centered … it’s only been focused on the rules,” she said.

Robinson’s Manor finally received a temporary license from Social Services almost seven weeks after De Johnette requested it, and the men moved into empty rooms at the women’s home in May.

Four months after the fires, their situation finally seemed to be settled. But in August, the department called De Johnette to say that the state of emergency was over so the temporary permission to lodge the men was no longer valid. They had to move again.

Since early September, they’ve been scattered about, from West Covina to the city of Orange, which is nearly 50 miles away. The latest displacement has been especially hard for a 54-year-old resident who, De Johnette said, has recently begun suffering from more frequent seizures.

“He’s just having a really hard time,” she said.

Daniella Lake writes for Capital & Main, a nonprofit publication focused on inequality. It is published here with permission.