By Ray Richardson

Contributing Writer

LOS ANGELES — Out of all the remarkable achievements Jim Brown was known for — never missing an NFL game in his nine-year career or leading the league in rushing a record eight times — it was an off-the-field huddle at his Hollywood Hills home that changed lives and strengthened Brown’s legacy as a true social activist.

Brown opened his patio doors on the night of Oct. 9, 1989 to about 75 people, most of them Bloods and Crips, members of the infamous rival street gangs in South Los Angeles.

The meeting kicked off Brown’s courageous movement to end gang violence and show the Bloods and Crips that there really is a better way of life in America.

“If it wasn’t for Jim, we probably would have blown up a building or something,” said Daoud Sherrills, a member of the Bloods who was at that meeting at Brown’s house. “That was our mindset back then. We thank him for that. Most of us haven’t been the same since.”

Brown’s efforts to decrease gang activity in Los Angeles led to a celebrated peace treaty in 1992 between the Bloods and Crips. When the NFL Hall of Famer died on May 18 at age 87, many of the gang members who came in contact with Brown remembered him more for saving their lives than what he achieved as a legendary running back or an actor in popular movies.

In fact, there are second and third generations of families who never saw Brown carry a football, but were well aware of Brown’s activism and push for social justice.

“I wanted to make changes in my life but didn’t know how,” said Skipp Townsend, a former Bloods member who is now the CEO and founder of 2nd Call, a job skills training organization in South L.A. “I heard about regular meetings Brown was having at his house. I saw guys I was shooting at and guys who were shooting at me. The things I heard enabled me to help myself.”

A year before hosting the landmark gang meeting at his house, Brown founded the Amer-I-Can Foundation, an organization dedicated to civil rights and providing resources and training for Black men coming out of incarceration.

Brown helped develop a training curriculum for inmates in Los Angeles County jails. Further training would be available for offenders after their release.

A spokesperson for Amer-I-Can said the organization is planning a “celebration of life” for Brown in June. The spokesperson added that there will be no public service or memorial for Brown.

In a recent TV interview, Brown said that he didn’t want a public tribute or service and preferred that his ashes be spread over the coast line near his hometown of St. Simons Island, Georgia.

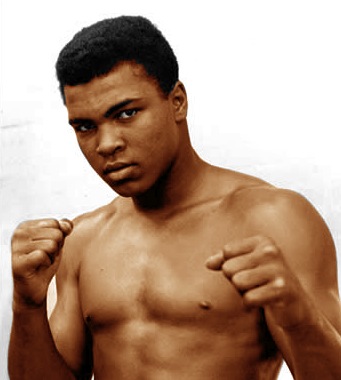

Brown’s activism became prominent in 1967, two years after he retired from the Cleveland Browns to go into acting. At a press conference in Cleveland, Brown joined NBA great Bill Russell, a rising college basketball star named Lew Alcindor, today known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and eight other Black athletes to show support for Muhammad Ali’s protest of the Vietnam War.

Ali refused to register for the draft, a stance that cost him his heavyweight title for three years. The appearance of Brown, Russell and Alcindor at Ali’s side led to a memorable photo that became known as the “Cleveland Summit.”

Brown’s activism and push for civil rights covered a range of domains — sports, politics, the judicial system and entertainment industry. But it was Brown’s willingness to get in the trenches and tackle gang activity that set him apart from other celebrities and activists.

“People like me, we didn’t know Jim Brown from football,” said Najee Ali, director of Project Islamic Hope. “We know him from caring about Black men and giving them the tools they need for success when they get out of jail.”

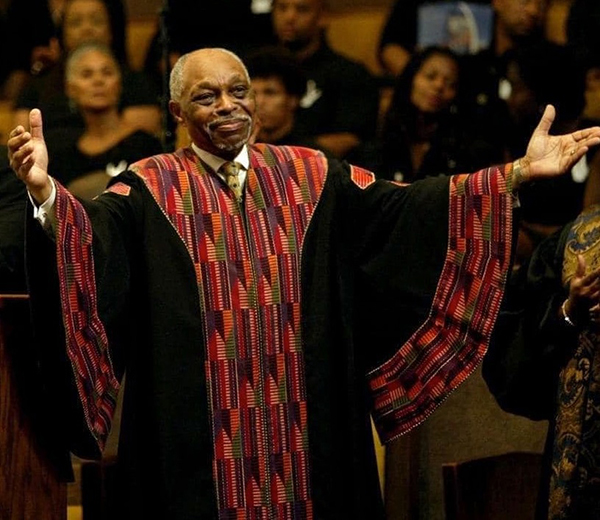

Sherrills’ brother, Aqeela Sherrills, a Bloods member, was also at the first gang meeting at Brown’s house. The meeting happened the day after Nation Of Islam leader Minister Louis Farrakhan made his “Stop The Violence” speech at the Los Angeles Sports Arena.

Brown wanted to immediately follow up on Farrakhan’s message and attack the gang problem head on. Farrakhan attended the meeting and brought some of his security team to make sure tensions between the Bloods and Crips didn’t escalate at Brown’s house.

“The meeting was smooth and prophetic,” said Aqeela, who today is executive director of the Community-Based Public Safety Collective, an organization based in Newark, New Jersey, that trains ex-gang members to be public safety professionals. “People were telling us it would be impossible to do, to get Bloods and Crips together in the same space to talk. That meeting was our cry for help. Those cries were falling on deaf ears.”

The success of the first meeting led Brown and his staff to set up regular meetings at his house on Wednesday nights over the next several years. Other celebrities visited occasionally to talk to the gang members, including Mike Tyson, George Foreman, rapper Big Daddy Kane and members of the rap group Public Enemy.

Jazz trumpeter Herb Alpert donated $100,000 to Brown’s efforts. People close to Brown recalled him spending as much as $400,000 of his own money to support his gang prevention work.

Years later, Daoud Sherrills had started a gang-prevention organization in Watts called Third Dynasty Egyptian Kings And Queens. Daoud said Brown paid the $350 rent for the organization’s office for the first seven months.

“Jim transformed us,” Daoud said. “A lot of folks gave us broken promises. Jim was sincere. He was real.”

Ray Richardson is a contributing writer for The Wave. He can be reached at rayrich55@gmail.com.