Kingdom Day Parade embroiled in controversy

Police Commission denies permit for longtime organizer

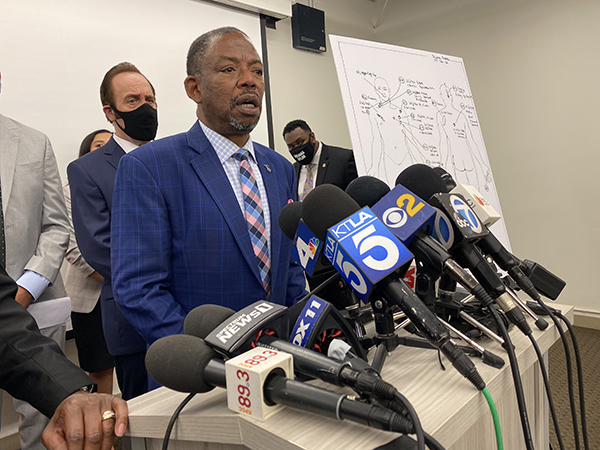

Adrian Dove waves to the crowd during the annual Kingdom Day Parade in the pre-Covid era. The longtime parade organizer says he is being squeezed out of running the annual parade for the coming year cecause of a tachnicality in the application process.

File photo

By Stephen Oduntan

Contributing Writer

SOUTH LOS ANGELES — The leadership of the upcoming Kingdom Day Parade became embroiled in controversy this week after the Los Angeles’ Police Permit Review Panel voted 4–1 Sept. 22 to uphold the denial of longtime parade organizer Adrian Dove’s application for next year’s parade, effectively squeezing him out of a position he has held for more than 20 years.

The panel said Dove technically violated the rules by submitting his application too early and awarded the traditional date and route to another applicant, Danny Bakewell of Bakewell Media, publisher of the Los Angeles Sentinel.

Sarah E. Bell, public information director for the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners, told The Wave that Dove’s application was rescinded because it was filed earlier than the six-month window allowed for First Amendment events. In a written response to questions, Bell said that a competing application was submitted properly and awarded on a first-come, first-served basis.

The Sept. 22 decision followed a Sept. 17 meeting that ended in a deadlock; panel members reconvened five days later and voted to uphold the denial. Bell added that Dove’s group, CORE, has now exhausted its administrative appeals.

Dove, 90, blasted the ruling as “absolutely unfair,” saying he was blindsided after first receiving written confirmation of approval on June 26, only to get a rescission letter in July.

“I’ve got both documents,” he said. “First they granted it, then they took it back.”

He said the process itself was contradictory.

“They told me I was too early, then went ahead and issued the permit,” he said. “Then they rescinded it and gave it to Danny Bakewell because he signed in hours before me the second time. What’s the solution to being too early? You sit on it until the date is right. Instead, they processed it, issued it, and then took it back.”

The veteran organizer accused Bakewell of waging a years-long campaign to acquire control of the parade, describing him as a figure who has “acquisitioned” other Black institutions, including the Brotherhood Crusade and the Sentinel itself. Dove said Bakewell’s filing used the very map and logistics he had developed over decades, from porta-potties to ambulance placements.

“They just lifted everything I built and put his name on it,” Dove said.

Dove also alleged that City Council President Marqueece Harris-Dawson has long sought to push him aside.

“Back around 2012, he told me I was too old to be doing this,” Dove said. “I was in my 70s then. Now I’m 90, and I’m still here.” He added that the council member’s “fingerprints are all over” the commission’s handling of the case.

For Dove, the fight is as much about symbolism as it is about permits. He said leaders of Pasadena’s Tournament of Roses once told him that the Kingdom Day Parade carried extraordinary symbolic weight.

“They said our brand was stronger — second only to Jesus Christ,” Dove said. “That’s what’s being taken away.”

Under Dove’s leadership, the Kingdom Day Parade has grown into what organizers call the nation’s largest and longest-running celebration of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., drawing 200,000 in-person attendees and more than a million television viewers.

Dove said his personal connection to King deepens the stakes. He recalled serving as one of King’s lieutenants during southern voter registration drives before working in the White House under four U.S. presidents. “

I’ve maintained my integrity all my life,” he said. “I don’t need to sell this parade for a check. I’m not in this for the money.”

The Kingdom Day Parade dates back to 1985 when Larry Grant, a retired military officer and banker, staged the first one in San Diego.

Several years later he relocated the parade to South Los Angeles where he was joined by Celes King III, the founder of the Congress for Racial Equality and Dove.

The parade’s transfer from San Diego to Los Angeles coincided with the renaming of Santa Barbara Avenue to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Dove, then president of CORE-CA, initially served as financial management officer. He had extensive experience as a senior budget examiner during his many years in the White House Office of Management and Budget and as a minority business development executive assistant and program developer under then-Mayor Tom Bradley.

Dove joined Celes King to bring in parade sponsors, until King’s death in 2003. Dove then continued to work on the parade with Grant, eventually becoming the head of the organizing sponsor of the Kingdom Day Parade.

When Grant died in 2012, Dove continued the role of chairman of CORE-CA and as chairman of the Kingdom Day Parade.

The parade has continued every year except for 2021 and 2022 when it was canceled due to the Covid pandemic. This year’s parade was held in February instead of January because of the wildfires that impacted much of Southern California.

Earlier this year, Dove said he would be stepping down as the lead organizer of the parade nut the ensuing controversy has brought him back in.

Looking ahead, Dove said he is considering relocating the parade to Inglewood or moving it to a different date but vowed to continue regardless of the venue. The uncertainty, he added, has already complicated sponsorship negotiations.

He also raised the possibility of one day transferring the parade to King’s children — but only if they reconcile their own disputes.

“I want to look up to Dr. King and tell him, I brought your children together,” he said. “I’ll give them the parade only if they drop the knives they’re pointing at each other and come together in love.”

King’s heirs have a history of disputes over their father’s Bible, Nobel medal and estate. With the death of Dexter Scott King in 2024, the surviving siblings — Martin Luther King III and Bernice King — remain the primary stewards of his legacy.

Dove urged Angelenos to reject the Bakewell-led version.

“Come to the real parade — to be determined — and boycott that one,” he said.

Bakewell Media acknowledged a request for comment Sept. 19, but did not provide a statement by press time.

Harris-Dawson’s office also did not respond to multiple phone calls and emails before publication.

The panel’s ruling raises the prospect of dueling parades in January 2026, with sponsors, broadcasters and elected officials potentially forced to choose sides. What began as a paperwork dispute now threatens to reshape one of Los Angeles’ most visible tributes to King’s legacy.

Stephen Oduntan is a freelance writer for Wave Newspapers.