By Jesse Jackson Sr.

Guest Columnist

On the eve of the Super Bowl, an event watched by millions around the world, the National Football League remains “rife with racism.”

In a league where nearly 70% of the players are African American, the NFL has not one African-American owner and only three African-American coach. Immensely profitable, professional football has the public relations savvy to try to whitewash a truly indefensible record.

Now, in an act of remarkable courage putting his own future at risk, Brian Flores, most recently the coach of the Miami Dolphins, has stood up, filing a class-action suit demanding change. Flores’ complaint details a compelling indictment.

The NFL was founded on racial exclusion, excluding Black players for many of its early years. When owners found that Black players made the game more exciting and increased revenues, they turned to running their franchises, as Flores’ complaint alleges, “like a plantation.”

White owners, general managers and coaches govern the largely Black players who take the field and run the risks.

For years — and even to this day to some extent – Black players were shunted from the position of quarterback, largely under the assumption that while they had better athleticism, they had less intelligence than white players. Similarly, Black players found it almost impossible to rise up to become offensive or defensive coordinators, much less head coaches.

Under pressure, the NFL devised what is called the “Rooney Rule,” requiring that any team hiring a head coach (now extended to offensive and defensive coordinators and general managers) must interview at least one candidate of color before making a hiring decision. If treated seriously, this rule could expand the pool to include qualified candidates of all races.

In the beginning, the Rooney Rule seemed to have an effect, and several Black coaches were hired. Today, however, there are only three Black head coaches.

What happened? The few Black coaches hired were held on a short leash. Flores reveals the astounding fact that Black coaches have been fired after having winning seasons in far larger numbers than white coaches. Flores himself was fired after leading the Dolphins to a winning record two years in a row.

The “Rooney Rule” interviews increasingly became sham interviews arranged for show, even after a white coach was already slated to get the appointment. After he was fired by Miami, Flores found himself interviewed for the head coach of the New York Giants — which has never hired a Black head coach — even after learning that the management had already settled on a white coach for the job.

NFL officials don’t even bother to deny this reality.

Troy Vincent, the NFL executive vice president of football operations, who is Black, said: “There is a double standard, and we’ve seen that. … And you talk about the appetite for what’s acceptable. Let’s just go back to … Coach Dungy was let go in Tampa Bay after a winning season. … Coach Wilks was let go after one year [at Arizona]. Coach Caldwell was fired after a winning season in Detroit. It is part of the larger challenges that we have. But when you just look over time, it’s over-indexing for men of color.

“These men have been fired after a winning season. How do you explain that? There is a double standard.”

With fans across the world rooting for teams based on the color of their jerseys rather than the color of their skin, this practice of systemic racist discrimination could damage the league’s reputation — and eventually the box office. The league’s response essentially is to admit they have a problem, and to promise — over and over and over again — to do better.

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell responded to the Flores lawsuit, saying, “We understand the concerns expressed by Coach Flores and others this week. … We must acknowledge that particularly with respect to head coaches, the results have been unacceptable.”

So, he promises to bring outside experts in to “re-evaluate and examine all policies, guidelines and initiatives relating to diversity, equity and inclusion.”

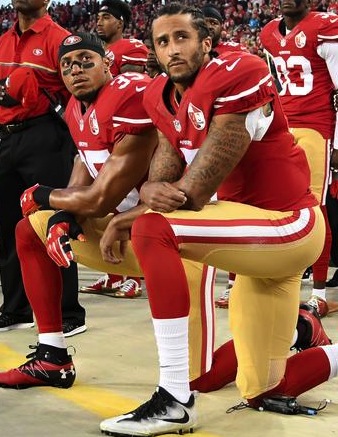

This is just another page from the same playbook of a league that ostracized Black quarterback Colin Kaepernick for expressing his solidarity with Blacks protesting racial injustice. Then, after the murder of George Floyd unleashed massive demonstrations across the country, Goodell released a video statement that “Black Lives Matter” and suggested the NFL wanted to work with Kaepernick in the creation of a multimillion-dollar foundation for social justice, even as Kaepernick remained excluded as an object lesson to other players.

Flores grew up in the tough streets of Brownsville in New York City. Asked if he worries about putting his career at risk, he said he understood the risks, but it was time for someone to stand up.

His lawsuit calls for structural changes in the way the league operates, from opening up ownership to qualified Black investors to changing the way coaches are hired and fired. Whether the lawsuit succeeds or not, by speaking out and standing up, Flores has already made a difference.

When you watch the Super Bowl Feb. 13, remember — amid all the pageantry, the fireworks, the advertisements, the halftime show, and the game itself — this is a league still stained by a pervasive racism that even its own officials cannot defend.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. is president and founder of the Rainbow Push Coalition.