Officers who killed Black motorist won’t face charges

District Attorney Nathan Hochman is taking heat from justice advocates for dismissing a case against two Torrance police officers who shot and killed a man seated in a car in 2018. Hochman said a key piece of evidence was inadmissable, making it hard to convict the officers.

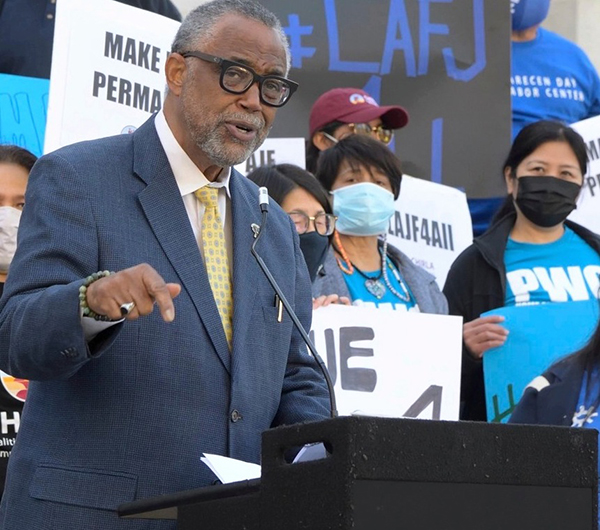

Courtesy photo

By Stephen Oduntan

Contributing Writer

LOS ANGELES — For many Black Angelenos, the story sounds familiar: a young man is killed by police, an investigation drags on for years, charges are filed — and then prosecutors quietly step back.

Advocates say the cycle has played out so often that trust in the county’s justice system has thinned to a thread.

That pattern resurfaced last week when on Nov. 21, Los Angeles County District Attorney Nathan Hochman moved to dismiss voluntary manslaughter charges against two Torrance police officers involved in the 2018 killing of 23-year-old Christopher Deandre Mitchell. Officers Matthew Concannon and Anthony Chavez shot Mitchell while he sat in what police believed was a stolen car, with an altered air rifle positioned between his legs.

A ruling on the dismissal had been expected Nov. 20, but a Superior Court judge postponed the hearing because the officers have a related petition pending before the California Supreme Court — placing the case in temporary limbo.

The case — first declined under former District Attorney Jackie Lacey, revived and indicted under her successor, George

Gascón, and now targeted for dismissal — has become a touchstone in the debate over whether Los Angeles County meaningfully pursues charges when officers fatally shoot Black men.

Civil rights leader Earl Ofari Hutchinson, president of the Los Angeles Urban Policy Roundtable, said Hochman’s decision “continues the pattern of giving virtual open license to police officers to use deadly force in dubious cases.”

“The decision to initially prosecute the officers was made after a substantial investigation,” Hutchinson told The Wave. “Hochman could and should have proceeded with a prosecution and let a judge and jury decide whether the officers’ use of deadly force was warranted. By taking that decision out of their hands, it signals once again that officers face no real consequences.”

Hochman insists that his hands are tied. A 26-page memo by special prosecutor Michael Gennaco, a longtime police use-of-force expert, concluded that key evidence was inadmissible — specifically, material relating to “officer-created jeopardy.” Without it, Gennaco wrote, prosecutors cannot prove the officers did not reasonably believe Mitchell was reaching for a weapon.

Hochman also faulted the prior administration for missing the statute of limitations on involuntary manslaughter. According to the memo, Gascón’s team allowed the three-year deadline to lapse before presenting the case. Without that lesser charge, Hochman argued, the remaining voluntary manslaughter count could not be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Mitchell was killed three years before the Torrance Police Department became embroiled in a racist-text messaging scandal that later came to light. According to the dismissal memo, Officer Chavez sent three racist or derogatory messages, including one using a slur against Black people.

Concannon did not send racist messages and at times muted the threads.

Prosecutors concluded the text messages would have added little to the case if presented at trial.

Hutchinson didn’t address the scandal directly but said decisions like these deepen the perception in Black communities that officers “face no penalty” when they kill young Black or Latino men.

“It tells police officers — no matter their color — that there will be no penalty when deadly force is used again, whether it’s warranted or not,” he said.

Hutchinson argues the district attorney’s rationale misses the broader point: public trust depends on prosecutors being willing to take difficult cases to trial.

“The prior DA didn’t pull this case out of the sky,” he said. “There is never a guarantee in any criminal case of conviction — but that doesn’t mean you don’t prosecute. Hochman should have been duty-bound to follow through.”

In a press advisory Nov. 24, Hutchinson said Hochman is “batting zero on police officer misconduct prosecutions,” calling the move a “license to overuse deadly force.”

With the case paused pending the Supreme Court petition, Hutchinson said the message to Black communities is unmistakable.

“It simply reaffirms the view, rightly held by many Blacks, that when it comes to Black life and the police, there is always imminent danger,” Hutchinson said.

Hochman’s decision not to try the Torrance case came days after a downtown Los Angeles jury could not reach a verdict in the trial of a former Whittier police officer who was accused of shooting an unarmed suspect who was running from a traffic stop in April 2020.

In that case, the jury was split 7-5 in favor of guilt on two of the charges and 8-4 in favor of guilt on the other two charges against Salvador Murillo.

The 44-year-old former detective was charged with two felony counts each of assault with a semiautomatic firearm and assault under the color of authority, along with allegations that he caused great bodily injury.

Murillo’s victim, Nicholas Carrillo, was shot twice in the incident with one of the bullets severing his spine, leaving him paralyzed.

Hochman has until January to decide whether to retry Murillo.

Stephen Oduntan is a freelance writer for Wave Newspapers.