By Earl Ofari Hutchinson

Contributing Columnist

What’s almost as terrifying as the targeted murder of 11 African Americans in Buffalo, New York May 14 by the alleged shooter Payton Gendron, is his age and the motive behind the mass racial murder.

Gendron is only 18. So young, but yet so imbued with every hodge-podge, crack-pot, hate-filled racist theory about Blacks. The theory, if it can be called that, even has a name, “The Great Replacement Theory.”

The theory holds that there is a great conspiracy by unknowns to replace whites with Blacks, Hispanics, and non-white immigrants. In short, they pose a great threat to America as a white man’s country.

Gendron is hardly part of a small group of kooks, cranks and nut cases that subscribe to this belief. A recent report by the Associated Press and the nonpartisan and objective research organization NORC at the University of Chicago found that a staggering one out of three Americans, presumably white Americans, are convinced that there is a move afoot by unnamed conspirators to replace them in the country.

They claim the purpose is to dilute if not eliminate whites as a political factor in the life of the country. It’s hate stuff pure and simple and Gendron didn’t just spew this stuff, he took it to its illogical extreme by committing mass murder presumably to eliminate some of those minorities, who the demented spinners of these goofball racist theories believe are out to get whites.

There was one more fact almost as disturbing about the Buffalo mass murder. That is the always cautious reluctance to officially brand these type of targeted mass murders by white extremists as hate crimes. There is absolutely no doubt this was just that.

Gendron had carved the word “nigger” on his assault rifle. There was his manifesto, hate filled rants about Blacks and Jews allegedly plotting in conspiracies against red-blooded white Americans.

The reluctance to fully crack down on obvious racist murderers has nothing to do with government recalcitrance, indifference, buck passing or a racial cover-up. It has everything to do with painful decisions on when and how hate crimes can be prosecuted, and even what really constitutes a hate crime.

Hate crimes and their prosecution is a muddled, hazy area clouded by the narrowest of narrow federal legal statutes, and worse, politics.

In the case of the Buffalo mass murderer, there was no specific named victim or target of the racial animus. That’s the absolute minimum requirement for considering what is and what can be prosecuted as a hate crime. Even pillorying someone with racial epithets while committing a physical assault against them might not pass the legal muster of what is a hate crime.

The crucial element is whether the racial epithets shouted at the victim were incidental to the attack or were they the precipitating factor in the attack? It’s the finest of fine legal hair splitting. Ultimately, that’s what prosecutors rightly or wrong look at in deciding whether they have any chance to get convictions in crimes where race is involved.

Then there’s the even more muddled picture of how much actual hate violence there really is in America. The Buffalo mass shooting doesn’t seem to be enough to warrant pushing the panic button. But it should.

The FBI annual hate crime report in 2021 found hate crimes had soared to their highest level in more than a decade. No surprise, the greatest majority of the hate crimes were against Blacks.

Civil rights leaders pound the Biden administration to bump up the number of hate crime prosecutions. And they should. Justice Department figures show a consistent drop in hate crime investigation referrals.

But President Joe Biden is hardly the only president that didn’t make hate crime prosecutions a priority. The White House foot-dragging on hate crimes has nothing to do with racial double standards and everything to do with politics and practicality.

Federal prosecutors have rarely placed much stock in bringing criminal civil rights cases. They see them as no-win cases with little political gain, and the risk of making enemies of local police, district attorneys and state officials.

The rare time that the feds cracked down on civil rights violence was during the 1960s civil rights battles. The wave of violence stirred national and international revulsion and forced then-President Lyndon Johnson to order more civil rights prosecutions.

Though federal prosecutors in recent times have had more than sufficient legal ground to bring cases in the old race murders from the 1960s, the prosecutions have been almost exclusively in state courts. The only exceptions to the hard-nosed rule that prosecutors stay out of state cases occurs when a hate crime triggers a major riot, generates mass protests or attracts major press attention.

That’s what happened in the case of Ahmad Arberry. When prosecutors anywhere try to sort out whether a crime is a hate-motivated crime, just plain crime or no crime at all, the question about hate becomes even more muddled.

The Buffalo mass murder case, though, should put an end to that muddle. It demands a swift and vigorous response. Gendron is a hate crime murderer and must be prosecuted as such.

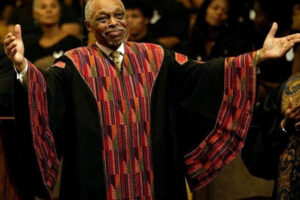

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is an author and political analyst. His forthcoming book is “The Midterms: Why They Are So Important and So Ignored” (Middle Passage Press). He also is the host of the weekly Earl Ofari Hutchinson Show on KPFK 90.7 FM Los Angeles and the Pacifica Network Saturdays at 9 a.m.