Local panel to study Black reparations is part of a growing national movement

By Janice Hayes Kyser

Contributing Writer

LOS ANGELES – Last week’s creation of a local task force that will draft plans for Black reparations represents the latest step in a movement that’s building momentum across America, due in large part to the explosive racial justice movement of the last year.

Mayor Eric Garcetti, who launched the Reparations Advisory Commission on June 18, said cities like Los Angeles should no longer wait on the federal government to do something they can clearly do for themselves — provide restitution for past injustices against Black residents.

“This work is long overdue. We cannot rely on Congress alone to influence this change,” said Garcetti, referencing a House bill that seeks to establish a commission to study reparations for Black Americans. “Local communities must act, too — and Los Angeles will lead by example in the movement to expose and dismantle structural racism.

Reparations alone won’t undo a legacy of inequity in America, Garcetti said, but it can provide structural remedies for the injustices it has caused. His action — coupled with his announcement of a coalition of 11 urban mayors who support reparations — is the latest step in a movement that started more than 30 years ago when U.S. Rep. John Conyers first introduced a reparations bill in the U.S House of Representatives.

Experts say the growing resolve of public figures across the country signals that reparations for slavery and historic racism in the U.S. — once on the edges of the nation’s political discourse — is slowly moving into the mainstream.

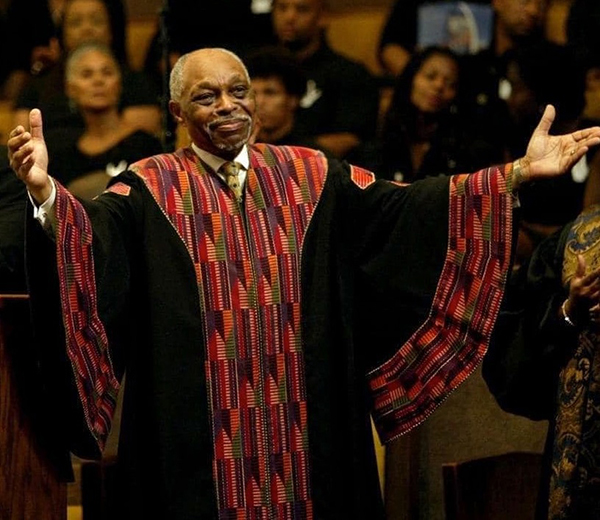

“We are witnessing a pivotal moment in the movement,” said Ron Daniels, convener of the National African American Reparations Committee, (NAARC). “Reparations has gone from being a fringe topic in the American political discourse to being a mainstream topic that is gaining support from all corners of the country.”

Daniels said the racial justice movement of the past year represents a “wakeup call to many who are finally understanding the truth. They are finally grasping the enormous economic, psychological and spiritual damage that needs to be repaired.”

In California, the state legislature in April voted to restore Bruce’s Beach, a Black beach resort in the early part of the 20th century, to the Bruce family that operated it. The city of Manhattan Beach had used eminent domain to seize the property from the Bruce family in 1929.

Like Los Angeles, other cities are no longer waiting on the federal government to take action and are establishing a spirit of atonement on their own — cities like Providence, Rhode Island; Evanston, Illinois; Asheville, North Carolina; and Detroit, Michigan.

In March, officials in the Chicago suburb of Evanston released funds from the first-ever national program offering reparations to Black residents. That program used a tax on legalized cannabis to offer home loan assistance to families that suffered the effects of decades of discriminatory housing practices.

“We had to do something radically different to address the racial divide that we had in our city, which includes historic oppression, exclusion and divestment in the Black community,” said Alderman Robin Rue Simmons.

“Evanston has a reputation as being progressive, yet the disparities between Black residents and white residents is deep — and that isn’t unique to Evanston, it exists in cities across this country.”

The first initiative of Evanston’s $10 million plan is the Restorative Housing Reparations program, which would distribute up to $25,000 for housing per eligible resident, Simmons said.

Daniels said reparations, like the discriminatory practices that necessitate it, can and should come in many forms. He said jurisdictions around the country are at different stages in their journey to find justice.

In Detroit, City Council President Pro Tem Mary Sheffield submitted a Reparations Resolution she says acknowledges that African Americans have been systematically oppressed and harmed through slavery, segregation, policing, incarceration and voter suppression.

In Asheville, city leaders committed $2.1 million toward reparations, an initiative it began last summer when it joined several U.S. cities that voted to address histories of racism and discrimination. The money will be drawn from proceeds the city acquired through land it sold as part of urban renewal programs of the 1960s and 1970s, which devastated Black communities in the city.

In Providence, where the city has been in what it calls the truth-telling phase, city leaders unveiled the results of a study that detailed the slave history of Rhode Island. The city’s mayor, Jorge Elorza, is one of the 11 mayors joining Garcetti’s national coalition to make amends to African Americans.

Los Angeles Urban League President Michael Lawson, a member of Garcetti’s task force on reparations, said studies without actions are “clearly not what we need,” progress can begin “with acknowledging the truth.”

“The saying that the truth will set us free, is certainly true.”