Watts residents demand answers as $850,000 pollution settlement sits idle

WATTS — In 2023, the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office secured a $2 million settlement from Atlas Iron & Metal, a metal recycling yard cited for hazardous waste violations.

The funds were divided three ways: $1 million for the Los Angeles Unified School District as restitution, roughly $200,000 in fines and penalties, and $850,000 earmarked for agencies and community groups to mitigate pollution or improve the quality of life in Watts.

That final portion, according to the district attorney’s office, is being monitored by City Councilman Tim McOsker’s staff.

But in Watts — a community long treated as a dumping ground — the real controversy began after the check was cut.

While $850,000 was earmarked for “community benefit,” residents and advocacy groups say they were never consulted on how the money would be used.

Court records confirm that $1 million of the Atlas settlement went to LAUSD, primarily for improvements at Jordan High School. Another $150,000 went toward enforcement efforts. But the $850,000 earmarked for “community benefit” remains loosely defined, with no public list of grantees.

Jeanne Min, McOsker’s chief of staff, confirmed in an email that their office “has not been provided with when or what amount of the funds will be administered … for the benefit of local organizations in Watts.”

Once the city receives confirmation from the district attorney’s office, she said, they plan to “establish a process for application, evaluation and distribution of funds,” emphasizing that it will be open and transparent.

But Watts resident feel they are getting the run around when they ask about the community benefit funds.

“We weren’t at the table. We weren’t even in the room,” said Tim Watkins, president of the Watts Labor Community Action Committee.

Watkins confirmed that neither his organization nor several others with deep roots in Watts were contacted during the allocation process.

“When you exclude the people who’ve been fighting these battles for decades, you’re not repairing harm — you’re just repeating it,” he said.

Watkins and others say the case reflects a deeper pattern: restitution dollars flow through political intermediaries, while impacted residents are sidelined — or erased entirely.

The settlement is the latest chapter in how environmental justice often bypasses the very communities it claims to serve.

Navaline Smith, a former resident of the now-demolished Ujima Village housing complex near the Watts Towers, remembers when she first learned the land beneath her home was contaminated. Exxon tanks buried underground had leaked, sending toxic vapor into the soil.

Dozens of residents, she says, later died of cancer. Her daughter lost half her throat to tumors doctors directly linked to the exposure.

“My daughter had to get half of her throat removed,” Smith said. “The doctor told us, ‘Wherever you were staying — whatever kind of soil it was — that’s the reason she has tumors.’ It was the soil. Ujima Village.”

Smith refused the county’s relocation offer of $1,500 and a Section 8 voucher. Instead, she stayed behind, fought in court, and eventually won a modest housing settlement. But most families left without compensation.

“They moved us in to die,” she said. “And then they erased us.”

Now living in Compton, Smith continues to advocate for survivors of Ujima Village. Her book, “The Last Lady Standing in Ujima Village Housing,” captures the raw aftermath of displacement with no meaningful restitution. Despite promises from officials, she says the community never received lifetime medical care or a formal apology.

Public health experts warn that Watts is not alone.

Dr. Bita Amani, a public health professor at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, said these stories are tragically common in communities like Watts, where redlining, zoning and environmental neglect intersect with race and poverty.

“We see clusters of cancer, asthma, birth defects, chronic illness,” Amani said. “You don’t need a smoking gun when the entire system is on fire.”

She described the contamination beneath Ujima Village as a textbook case of environmental racism.

“When we talk about structural violence, this is what we mean,” she said. “These aren’t isolated incidents. They’re the predictable outcome of decades of land-use decisions that place polluters next to homes, schools and parks in Black and brown neighborhoods.”

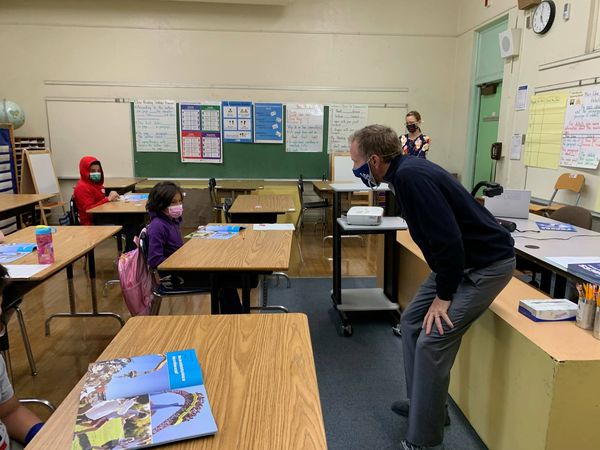

For Genesis Cruz, a 20-year-old Watts native and environmental justice advocate, the harm is still unfolding. She grew up near Jordan High School — just blocks from Atlas — and began organizing in high school after learning about local contamination.

“I grew up being told, ‘Don’t play in the dirt, don’t drink the water, don’t breathe too deep,’” Cruz said. “Imagine being a kid and already knowing your environment is working against you.”

For longtime residents, the pattern of being last to know — and first to suffer — has worn thin.

William Taylor, a Vietnam veteran and lifelong Watts resident, lives just blocks from the Atlas site. He says local people like him are tired of government officials showing up only when the cameras are on — or not at all.

“I’ve seen neighbors die from this stuff, and not once did anyone from the city ask us what we needed,” Taylor said. “They think we don’t matter.”

Taylor’s frustration is echoed by others, some of whom have attended city meetings or read news releases only to discover decisions had already been made.

“There’s no accountability,” Taylor said. “They make promises, but the damage is done. And the people living here? We’re left with nothing but sickness and silence.”

Stephen Oduntan is a freelance reporter for Wave Newspapers.