By Janice Hayes Kyser

Contributing Writer

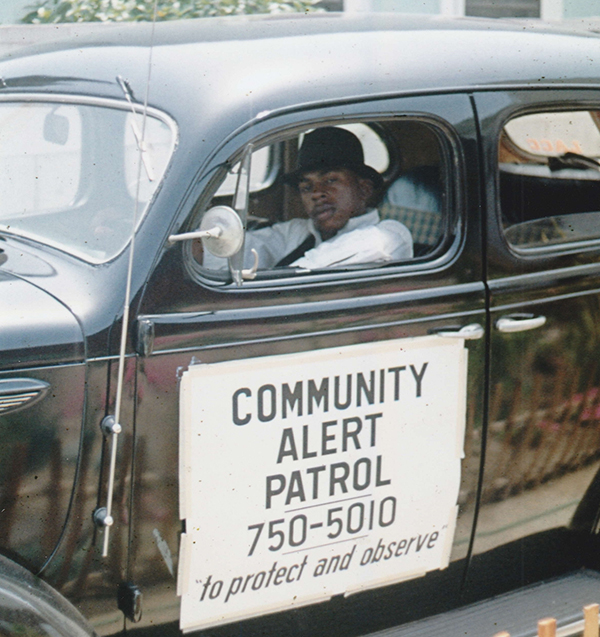

Following the 1965 Watts riots, South Los Angeles was hurt and broken. Not only were buildings destroyed, lives were devastated and the spirit of the community was shattered.

That’s when women like Mary B. Henry dedicated their lives to rebuilding the community from the ashes. Like their ancestors before them, these “mothers of the movement” committed their lives to fighting for the rights of others.

Henry’s lifelong crusade to provide quality education, health care and social services to the poor in South Los Angeles left a lasting legacy in the community and her name is on facilities serving the needy.

Editor’s note: The phrase “Black Girl Magic” has dominated social media in recent months, fueled again last month when Kamala Harris, Michelle Obama and Amanda Gorman embodied Black elegance during the presidential inauguration of Joe Biden. So this Black History Month, we focus our coverage on the women trailblazers and “sheroes” from America’s past who paved the way for Harris, Obama, Gorman and millions of other Black Girl achievers today.

While her focus was local, she played a pivotal role in the development of the King/Drew medical complex and was probably best known for catering to local needs as director of the Avalon-Carver Community Center serving South L.A., her influence extended beyond the city of angels. She served on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty task force and that led to the creation of the Head Start Program, which offers early childhood education and nutrition to inner-city youth.

Another fierce advocate for South L.A. was Lillian Mobley. U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters called her the “most accomplished and successful community activist South Los Angeles has ever had” and a voice for “poor people and working folks.”

Like Henry, Mobley was one of a group of determined women who pushed to build a major hospital in South L.A. as well as a medical school. Although Mobley’s focus was on Watts, her influence reached throughout the city where she sat on boards and councils tackling issues ranging from transportation to education, health care, services for the elderly and water rates.

Juanita Tate brought her talents and tenacity to South L.A. neighborhoods in the 1980s and 90s where she worked tirelessly to build affordable housing, help establish a credit union and advocate for environmental justice and green spaces. Her success in blocking an incineration plant from being built in the community led her to launch Concerned Citizens of South-Central Los Angeles.

When it comes to fighting for the Black community, Black women have always hit the pavement and paved the way, says Michael Lawson, president and CEO of the Los Angeles Urban League. Lawson says one of those unsung women is Katherine Barr, who was instrumental in founding the L.A. Urban League in 1921 and was the organization’s first leader.

Barr, a graduate of Tuskegee Institute, focused the Urban League on the issue of infant mortality that continues to plague the Black community today. Like the Urban League in Los Angeles, women, including activist Betty Hill, also played a role in founding the L.A. chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1913.

“Black women activists have been leading the way since Harriet Tubman,” Lawson said. “I am happy for the recognition sisters are getting, but it is long overdue. They will continue to do the work because service is in their DNA.”

For Black women in Los Angeles that call to community service dates back to the 1850s when freed slave Biddy Mason settled in Los Angeles. Mason not only used her earnings from working as a day nurse to amass property and eventually become one of the wealthiest women in the city; she also gave back to the community, explains Marne Campbell, associate professor and chair of African American Studies at Loyola Marymount University.

According to Campbell, when Mason died, her obituary acknowledged her as a community leader, a woman who overcame extreme adversity, and a generous caregiver. As a philanthropist, Mason started initiatives that provided food and shelter for African Americans. Mason routinely visited prisoners in the local jail, and patients in asylums and hospitals. She is well known for having provided the funds to secure the property for the construction of the first African-American church in the city, First African Methodist Episcopal Church (FAME), in 1872.

That drive to stand up for the civil rights of others lives on today in the work of Black women across the city both behind the scenes and on the front lines.

Melina Abdullah, co-founder of the L.A. chapter of Black Lives Matter and chair of the department of Pan-African Studies at Cal State Los Angeles, is one of the most visible and vocal voices in the fight for equality and justice in L.A. and beyond.

Keyana Celina’s voice and efforts have been focused on fighting police brutality as part of the Coalition for Community Control of the Police.

The vicious 1991 beating of her father, Rodney King, at the hands of Los Angeles Police, is what catapulted Lora King into the movement. The acquittal of the four LAPD officers by an all-white jury in April 1992 sparked outrage and riots and a nationwide call to end police violence against the Black community.

Today, almost 30 years later, Lora is keeping the memory of her deceased father alive through the Rodney King Foundation, which advocates for social justice and human rights causes in L.A.

Constance L. “Connie” Rice is a civil rights activist and lawyer who leverages her legal acumen and unconventional approaches to expand opportunity and advance the cause of equity and justice. She is co-founder and co-director of the Advancement Project, a multi-racial grassroots organization committed to rooting out racism and transforming justice for people of color.

Alice Harris, also known as “Sweet Alice,” is another prominent activist in the city who has made it her life’s work to assist the underserved. She is the executive director of Parents of Watts Inc., a social service organization she started out of her home in the 1960s to help ease the tensions and toll of the 1965 Watts riots on her community.

Since that time Harris and other volunteers have been providing emergency food and shelter, preparing teens for college and jobs and offering drug counseling, health seminars and parenting classes.

Lawanda Hawkins, who formed Justice for Murdered Children, a nonprofit group that advocates on behalf of Black and brown murder victims and their families after her 19-year-old son was murdered in South L.A. in 1995 is yet another example of the selfless advocacy Black women possess.

“It’s not about me and my son,” Hawkins said. “Sure, he was my only child and the love of my life, but it is about the greater good.”

Hawkins’ organization worked tirelessly on behalf of Marsy’s Law, the California Victims’ Bill of Rights Act that was passed in 2008.

“We belong to a club we never wanted to join,” she said. “We fight because we are the mothers of our community.”