By Edward Henderson

Contributing Writer

LOS ANGELES — Photographs serve as historical records, framing both big moments and small ones with images that evoke a range of emotions such as passion, sadness, joy, nostalgia and more, connecting us emotionally to the history captured in them.

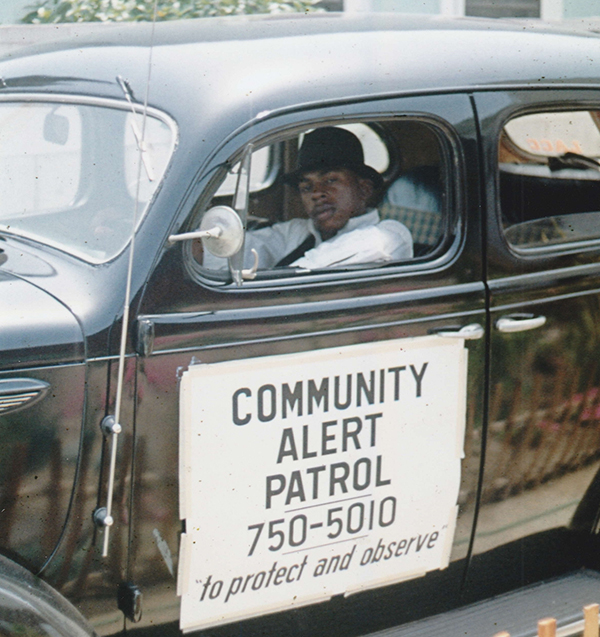

L.A.-based photographer and organizer Ron Wilkins, 78, showcases powerful images he captured from the Black liberation movements of the 1960s and beyond in his new book “Crook’s Lens: A Photographic Journey Through the Black Liberation Struggle,” published in January.

Wilkins’ book includes photographs of renowned revolutionaries with whom he interacted, including Huey P. Newton, Angela Davis and Stokeley Carmichael (aka Kwame Ture).

“I have a responsibility to our African ancestors who struggled for our liberation, who made sacrifices and committed a lot of time,” Wilkins said. “Some of them lost their lives in that struggle.

“I felt as an activist/organizer after all these years that since I’m still alive, I have a responsibility. The book is also a reflection of my evolution and ongoing work,” Wilkins said.

“I felt it was important I share my history, especially with young people. They can learn something from my example and carry on the struggle.”

Wilkins was born in San Francisco, but his family relocated to Los Angeles in 1959. His peers gave him the nickname “Crook,” which is reflected in the title of his book. Constantly looking for ways to make money, Wilkins often resorted to stealing and reselling things.

“On a couple of occasions, guys would look at me and say, ‘you’re quite a crook,’” Wilkins said. “That’s how I got the name. When I became politically aware and became part of the struggle, people would often call me Brother Crook.”

Eventually, Wilkins started stealing cars.

One fateful night he was arrested and served eight months in a juvenile detention center. The harsh reality of that experience, he says, shook him to his core, steered him away from crime and kickstarted his journey as an artist with a revolutionary perspective.

He started to capture images of history-making moments through his lens. His subjects became some of the most influential Black organizers and activists of the time.

“When I was in detention, I noticed how segregated the place was and I spearheaded a movement on the part of Black inmates against those who were holding us, to end segregation in the pen,” Wilkins said. “That was 1963. After I was released and returned to the street, the Watts rebellion jumped off. That was the cauldron that helped me develop a revolutionary consciousness and decide to become a part of a movement to fight the system and do this for the rest of my life.”

In 1967, Wilkins joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee after that group began to embrace the principles of the Black power movement.

During his time with the group, Wilkins met a professional photographer within the organization. He began to learn more about photography. The chance meeting planted a seed of inspiration within him to capture images of the growing movement he was observing and in which he was participating.

“There is a saying ‘seeing is believing,’” he said. “I could tell you something but in the back of your mind you would think I’m just talking. But if I show you the image, the picture makes it very plain. That is the power of photography.”

Wilkins’ book chronicles his life story through a diverse collection of photographs, capturing his encounters with historic Black organizers in the liberation movement and his travels to Africa. However, his most prized photo is of five Black girls sitting on the porch of the Pyramid Housing Projects in Cairo, Illinois in 1972.

The housing project had been under attack by white supremacists in the area. Wilkins traveled to Illinois to serve as an armed patrolmen tasked with protecting the residents.

Additionally, Wilkins photographed Nina Simone, who was invited to lead a protest march through the heart of downtown, where white business owners were refusing to hire Black employees.

“One morning walking home from patrol, I ran across these five Black girls sitting on a step after a night of enduring all of this gunfire,” Wilkins said. “I saw them and said, ‘don’t move.’ I think it was the best picture I ever took. It captured so much feeling.

“Their facial expressions. Their spirits were still intact. They had a quiet courage that their bodies reverberated with. They could see hope in the future, even though they had endured a night of this intense gunfire.”

Wilkins’ hope is that his book will uplift the spirit of the young revolutionaries he photographed and inspire others to recognize that the struggle is not over. He also hopes it will remind young people that they can aspire to the same heights of passion, intelligence and bravery that define the lives of the heroes depicted in his photos.

Edward Henderson is a reporter for California Black Media.