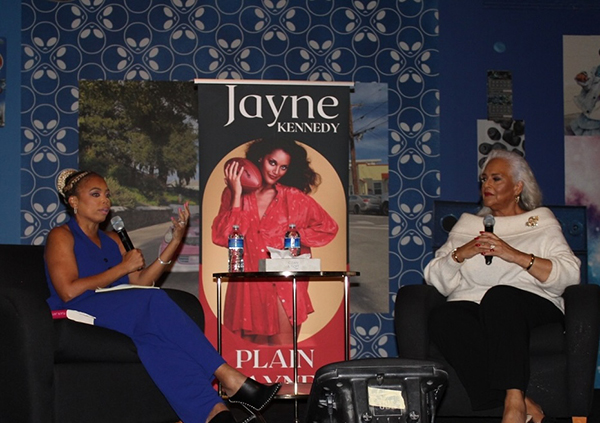

Dulan’s owner struggling to stay afloat

Owner Greg Dulan, left, speaks with a staff member inside the kitchen at Dulan’s on Crenshaw, a family-owned soul food restaurant facing a balloon loan deadline. Dulan’s has been a cultural anchor in South Los Angeles for more than three decades.

Photo by Stephen Oduntan

By Stephen Oduntan

Contributing Writer

CRENSHAW — On a recent afternoon inside Dulan’s on Crenshaw Boulevard, the phones never stopped ringing. Owner Greg Dulan juggled calls from suppliers, customers, and reporters, pausing only to underline the challenge that could define his restaurant’s future: parking.

“The K Line took away 400 parking spaces on Crenshaw,” he said bluntly. “I couldn’t wait for the city to do it. I had to solve it on my own.”

For more than three decades, Dulan’s has been a cultural anchor in South Los Angeles. The soul food restaurant — famous for its fried chicken, short ribs, and peach cobbler — has weathered recessions, neighborhood change and a pandemic.

But now the family-owned institution faces its most serious test: a balloon loan on two parcels Dulan purchased to keep his business viable.

Unless he can refinance or find an investor, the debt could wipe out years of work and jeopardize the livelihoods of his 34 employees.

Dulan saw the crisis coming years ago. The rezoning around the new K Line allowed high-rise apartments to be built with little or no parking. His own block was designated T3, requiring developers to provide only half a parking space per unit.

So he acted. Dulan purchased a former nursery school from high school classmates, planning to tear down part of it and create a 22-space parking lot. When the adjacent warehouse came on the market, he bought that too, envisioning a production kitchen that would expand his heat-and-serve meal business while doubling as a workforce training facility for young people.

“That way, I’d be providing a community benefit by adding much-needed parking while also training young people in catering, food production, and food truck operation,” he explained.

Then came the hard-money loans — high interest and a balloon payment. The remodel ran over budget and behind schedule, leaving him without funds to finish the parking lot. Now, the debt looms in the seven-figure range.

“The restaurant is doing great,” he insisted. “But the other parcels drained me. I thought I’d have help, but I ended up taking it on single-handedly. I’m not a developer — I was trying to remodel a restaurant and build a parking lot at the same time.”

He has already survived a gauntlet: the pandemic, years of street closures from K Line construction, and now the ongoing Destination Crenshaw project. Each setback added costs and delays.

Without a solution, dozens of jobs — and the ripple effect they carry for families in South Los Angeles — could disappear.

“They’re not replaceable,” Dulan said simply.

What he is asking for from the public is modest compared to the debt: eat at the restaurant, order on DoorDash, book catering.

“That’s what will help this week,” he said.

In a city where sit-down soul food restaurants are scarce, Dulan’s has become a rare gathering space. In recent weeks alone, it has hosted Rep. Sydney Kamlager-Dove, Mayor Karen Bass, City Council President Marqueece Harris-Dawson, the district attorney, and a clergy breakfast for 100 ministers.

“The community wanted a nice sit-down restaurant,” Dulan said. “I knew it could be risky, but I went forward because it was needed. And now I see how much people appreciate it.”

A Brooklyn native, Dulan says he has watched blocks turn over before and sees echoes of that on Crenshaw. He rejects the label gentrification, calling what’s underway “progress” that the corridor can harness.

“The K Line was the igniter,” he said. “Over the next five, 10 years, you won’t recognize Crenshaw.”

Many longtime residents and small-business owners along the corridor say the same changes look different to them — cranes rising, rents climbing, legacy shops feeling the squeeze — and they worry about displacement, a concern voiced in neighborhood meetings and on the block.

Dulan counters that his own project is meant to root Black ownership, not replace it: parking to keep customers coming and a production kitchen and training center to create jobs.

“People are still going to need a place to eat,” he said. “We’ll be here.”

Despite conversations with city and county leaders, Dulan said no concrete assistance has materialized. His message to policymakers is clear: “We have to protect our cultural heritage in Los Angeles — southern traditions — especially those that operate in food deserts.”

Years ago, a developer offered to buy his properties to make way for apartments. He turned it down.

“This was the community’s need,” he said. “They wanted a sit-down restaurant, and I went forward even knowing it could be risky. But I believe everything is going to be all right. This restaurant is going to be here serving the community long after I’m gone.”