By Ray Richardson

Contributing Writer

LOS ANGELES — When George W. Bush was president of the United States, he found out firsthand the level of commitment Rev. Cecil Murray had for his congregation and community.

Before leaving Los Angeles after a visit, Bush invited Murray to meet with him on his Air Force One jet that was parked at Los Angeles International Airport. Bush had spoken at Murray’s First AME Church on a previous visit.

Though honored with the invitation, Murray told Bush he couldn’t make it. The meeting conflicted with the Bible study class he taught.

“That showed the love he had for his people. … That he would pass on a meeting with the president to teach the word of God,” Mark Whitlock, pastor of Reid Temple AME Church in Glenn Dale, Maryland, said of his longtime mentor. “Pastor Murray was the Moses of our time. He was respected in the White House and on the streets.”

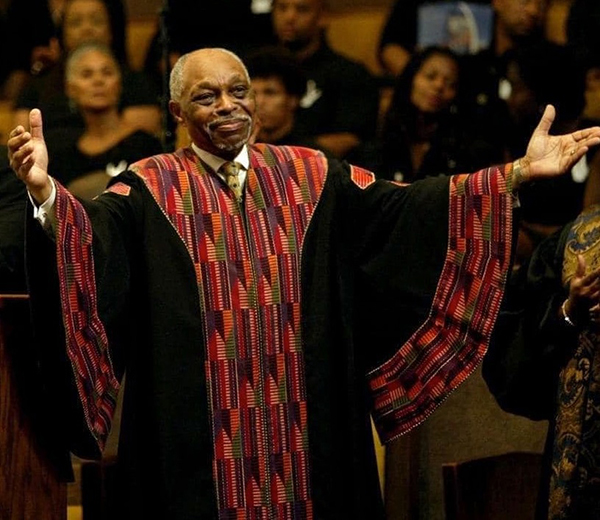

Cecil “Chip” Murray, who often left his pulpit to create peace between rival street gangs and more resources for Black communities in South Los Angeles, died of natural causes on April 5 at his home in the View Park-Windsor Hills neighborhood. He was 94.

As of April 10, funeral arrangements were pending.

Murray’s death led to an outpouring of tributes for a man regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of Los Angeles.

“We lost a giant,” Mayor Karen Bass said in a statement. “Reverend Dr. Cecil Murray dedicated his life to service, community and putting God first in all things. I had the absolute honor of working with him, worshiping with him and seeking his counsel. My heart is with the First AME congregation and community today as we reflect on a legacy that changed this city forever.”

Bass joined U.S. Senate candidate Adam Schiff and other dignitaries for worship service April 7 at the renowned First AME to honor Murray.

Bass is among several Los Angeles mayors that had close ties to Murray, including Richard Riordan and Tom Bradley. Bradley remained a member of Murray’s church until he died in 1998.

During Murray’s 27-year term as First AME pastor, he was revered by politicians, celebrities and civic leaders for his proactive roles in the community and push for social justice.

He retired as senior pastor at First AME in 2004 after reaching the age of 75, the mandatory retirement age for AME pastors.

Following his retirement, Murray embarked on a second career as a Tansey Professor of Christian Ethics and chair of the Cecil Murray Center for Community Engagement at USC from 2005 to 2022, where he trained more than 1,000 faith leaders in the “Murray Method,” which focused on tackling community needs by moving from what he called “description to prescription.”

“What he did will not be duplicated,” Ninth District City Councilman Curren Price said of Murray. “He was the kind of leader we needed at a time when our city was railing with police issues. Our challenge now is to rise up and carry on his legacy. It’s a difficult task but doable.”

Former Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton spoke at First AME, as well as Rev. Jesse Jackson, Nation of Islam leader Minister Louis Farrakhan and Nelson Mandela.

Murray extended invitations to these luminaries and others to enhance his mission of improving the communities where many of his congregation members resided.

“It was never about him,” former Los Angeles Urban League President Michael Lawson said of Murray. “It was always about doing what’s right for the community and how his church could be a part of it. He went beyond. He wanted to use the church as a catalyst.”

Murray expanded First AME’s outreach in 2001 when he opened the FAME Renaissance Center, a multi-purpose facility located just two blocks from the church. Whitlock was president of FAME Renaissance Center for 13 years. He and Murphy brought in staff to help develop a variety of community programs and services.

Among the components at FAME were job skills training classes, employment assistance for ex-offenders, free legal aid, housing and clothing resources and other services.

Many of Murray’s supporters cite the FAME Center as one of his crowning achievements. Murray developed the FAME Center in response to his concerns about the lack of Rebuild LA funding coming into Black communities after the riots in 1992.

Murray was at the forefront of efforts to maintain peace on Los Angeles streets after four LAPD officers were acquitted in the videotaped beating of Rodney King. Despite numerous financial commitments from businesses and governmental agencies, Murray still saw inequities in Black communities.

Murray was born on Sept. 26, 1929, in Lakeland, Florida.

He earned his undergraduate degree from Florida A&M University in 1951 and joined the U.S. Air Force after graduation where he served during the Korean War as a jet radar intercept officer in the Air Defense Command and as a navigator in the Air Transport Command.

Murray retired as a reserve major in 1958 and was decorated with a Soldier’s Medal of Valor.

He earned his Ph.D. in religion from the School of Theology at Claremont College in 1964 and served as a pastor at churches in Pomona, Kansas City and Seattle before coming to FAME in Los Angeles where he showed up sporting an Afro and a dashiki and started to transform the church from a staid congregation of traditional hymns and little civic activism to one that included drums and guitars during services.

Under his leadership, First AME was named one of President George H.W. Bush’s 1,000 Points of Light, a nonprofit initiative the president started during his term of office.

“Pastor Murray always believed that you have to work beyond the walls of the church if we’re going to be real servants,’’ said Kerman Maddox, managing partner of Dakota Communications and a First AME member since 1985. “He felt the church needed to go where the problems are and try to make a difference.”

Maddox was with Murray one day in the late 1980s when Murray decided it was time to meet some issues head on. At the top of Murray’s list was the rising crisis of street gang violence, particularly the ongoing battles between the infamous Crips and Bloods.

Murray led a walk to the Avalon Housing Projects near Watts in a bold attempt to negotiate a truce and end Black-on-Black crime.

“I remember seeing a lot of red and blue when we were walking,” Maddox said. “It was pretty scary, but it didn’t stop Pastor Murray.”

There were numerous other times Murray ventured into neighborhoods to spread messages of peace and healing. The results were often mixed, but the passion displayed by Murray earned respect from community and civic leaders and law enforcement.

“It seemed like under Murray’s pastorship, First AME was at the cutting edge of every significant issue in the community,” said Herb Wesson, former Los Angeles City Council president. “It’s hard to articulate the impact he had on South L.A. and the entire city.”

Murray’s wife of 54 years, Bernardine, who gave him the nickname “Chip,” died in 2013. His survivors include his son, Drew.

Ray Richardson is a contributing writer for The Wave. He can be reached at rayrich55@gmail.com

City News Service also contributed to this story.