By Shirley Hawkins

Contributing Writer

LOS ANGELES — Black women are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than white women, according to statistics from the Centers of Disease Control.

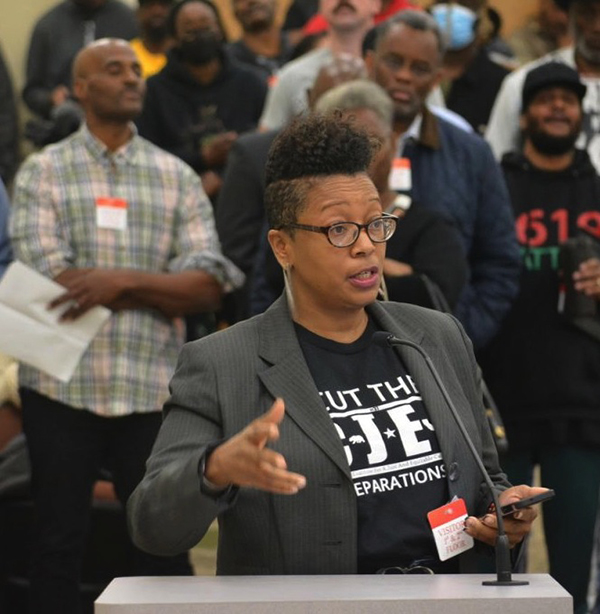

In an effort to combat the disparities in the treatment of expectant Black mothers and to raise awareness about the problem, the Black Women for Wellness held their 24th annual Reproductive Justice Conference at the California Endowment Center Aug. 10 with the theme of “Healing From Our Past Protecting Our Present and Preparing for Our Future.”

The daylong conference included a well-attended maternal health semnar entitled “The Realness of the Maternal Infant Health Crisis,” in which several panelists recounted stories of hospitals and medical personnel that failed to deliver proper care to themselves as well as other Black mothers and infants resulting in fatalities.

Panelists included Freddie Cromer, a father of five whose wife died at a hospital during her pregnancy; Toy Hightower, program coordinator of Care First Community Investment African American Infant and Maternal Mortality Prevention Initiative for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health; Bree Anderson, co-founder of the Daughters Beyond Incarceration and Asani Heartbeat Foundation; Debbie Allen, a licensed midwife, founder of Tribe Midwifery and co-founder of Well-Being Alliance; and Ashley-Skiffer Thompson, program coordinator for the county Department of Mental Health.

Expecting the healthy birth of their fifth child, Cromer said he and his wife Bridget arrived at California Hospital Medical Center in Los Angeles last March 1 for a scheduled Cesarean birth.

“From the beginning, there were problems,” Cromer said. “The [doctors] and [nurses] didn’t know that we were coming and they didn’t have our medical records. That information really frustrated my wife.

“She started getting a headache and they took her blood pressure and they found out it was high. They admitted her into the hospital while they went to get her medical records from the Watts Healthcare Center and she was scheduled for a C section the next day.

During the C section, Cromer said his wife told him she wasn’t feeling well and she started sweating. The baby was born at 4:35 p.m., a girl named Divinity.

Later, in the recovery room, the doctor became concerned about Bridget’s low blood pressure reading and decided she was bleeding internally.

“Four hours later, they opened up her stomach and found two liters of blood,” Cromer said. “They eventually took out her uterus to try to stop the bleeding.”

But that didn’t work and Bridget died that night.

“The doctor who operated on Bridget has [had] five malpractice suits,” Cromer said. “She didn’t have the privileges to perform a C section and tubal ligation.”

Since his wife’s death, Cromer has become a staunch advocate for Black maternal health.

“It hasn’t been easy since my wife’s been gone trying to take care of the kids and trying to pursue justice for her at the same time,” he said. “It’s like nothing is being done [to improve Black maternity outcomes] and it upsets me and makes me angry. There’s no one else that wants to join my club because it’s been heartbreaking for me. But I’m just starting this fight.”

Bree Anderson, who flew in from New Orleans to attend the conference, said she found out she was pregnant in March 2022.

“After four weeks, I went to the doctor,” Anderson said. “They said it was twins — a girl and a boy. We were excited, we had a gender reveal [party].

“Two to three weeks later I experienced a slight pain, so I went to the hospital. The nurse said, ‘Don’t freak out. You are five centimeters dilated.’

“At that point I was only 24 weeks pregnant. The twins were born — one was one pound, 7 ounces and the other was just one pound. It was scary. I didn’t get the same moments and joy that most new mothers get.”

The baby girl didn’t survive the early birth. The boy was on oxygen for five months.

In honor of the girl, who Anderson named Asani, she started her nonprofit the Asani Heartbeat Foundation last August.

“I’m passionate about standing up for girls and women,” Anderson said. “I think women and girls are the most resilient people on the planet. I’m committed to them because a lot of people don’t stand up for us when it comes to navigating pregnancy just because we are Black women.

“Our agency helps to improve pregnancy outcomes and support high-risk pregnancies by providing families with mental health resources, advocacy, prenatal support and community baby showers,” she added. “I know what it is like to need support during a vulnerable time.”

Her son, Asir, is almost 18 months old.

“Everytime I look at Asir I see his sister too and that’s a gift and pain at the same time,” she said.

Researchers from George Mason University have analyzed data that found that when cared for by white physicians, Black newborns were about three times more likely to die in the hospital than white newborns.

“Black babies have been dying at disproportionate rates since as long as we’ve collected data,” said Rachel Hardeman, who co-authored the report. “It’s already known that Black infants have 2.3 times the infant mortality rate as White infants, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health.

“That disparity dropped significantly when the doctor was Black, although Black newborns nonetheless remained more likely than white newborns to die.”

Shirley Hawkins is a freelance reporter for Wave Newspapers. She can be reached at metropressnews@gmail.com.

CAPTION