By Cynthia Gibson

Contributing Writer

LEIMERT PARK — As a young Black woman in the 1970s, Phyllis Lynn Ellis was told that she had to work 150 days to be eligible for a Screen Actors Guild card. Obtaining a SAG card would allow her to pursue a career as a stuntwoman and receive benefits and screen credit for her work.

When Ellis tried to apply for a SAG card, her efforts were continuously rebuffed. She was repeatedly told she had arrived on the wrong day or she would work for 149 days and then wouldn’t be hired for two weeks, forcing her to start all over again.

“It was frustrating, but I loved the industry so I did everything I could to keep in there,” Ellis said.

However, there were some things Ellis refused to do to get her SAG card. She was propositioned on a number of occasions, but refused.

“I didn’t do what they wanted,” Ellis said.

In the end, Ellis never received her SAG card. Her 30-year career in the film industry included hundreds of independent uncredited stunts and behind the scenes jobs in hair, make-up and wardrobe.

Change came when the Black Stuntmen and Women’s Association was created in the late 1960s.

Association President Alex Brown said that Black and white women had a difficult time breaking into the industry.

“White women were discriminated against, too,” Brown said. “They just didn’t realize it.”

Until the late 60s, stunts for Black actors and actresses were done by white men in “paint down,” an industry term for covering white men with dark make-up. White men also donned wigs and performed stunts for white actresses.

“Black women caught a little bit more hell,” Brown said. “When we started to fight for our rights, we knew we had to bring women along and train them to do some of the same work that the white stuntmen were doing.”

Supported by the NAACP and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Black Stuntmen and Women’s Association filed and won 32 lawsuits in their fight for job opportunities in the film and television industry, including a 1976 case that forced the major studios to abide by federal mandates against discriminatory hiring practices.

The civil rights and social justice struggle by the association opened doors for men and women stunt workers along with job opportunities for minorities in other craft and guild crew positions with Hollywood film and television production companies.

Jadie David was spotted riding one of her horses in Griffith Park by a scout looking for a stunt double for actress Denise Nicholas. Like Ellis, David’s career also spanned more than three decades.

She was a stunt double for Theresa Graves in the 70s crime drama, “Get Christie Love.” She performed stunts for all of Pam Grier films including “Foxy Brown,” “Coffy” and “Friday Foster.” David also did stunt work for Cicely Tyson, Whoopi Goldberg and others.

David credited her successful career as a stunt woman to her height (she’s 5-9) and the fact that she had a similar build to a lot of women in film at the time. She also said that she became well known and did a lot of independent work.

“I was hired a lot as a nondescript person, meaning I could’ve been anybody,” David said. “That kept me working.”

As thrilling as stunt work can be, it is also very dangerous.

David has broken her back twice. Once in the 1977 disaster-suspense film “Rollercoaster,” when she jumped off the railing of a rollercoaster car. The second time was another fall during the filming of a television movie called “Truth or Consequences.”

“I don’t even know if that episode aired,” David said.

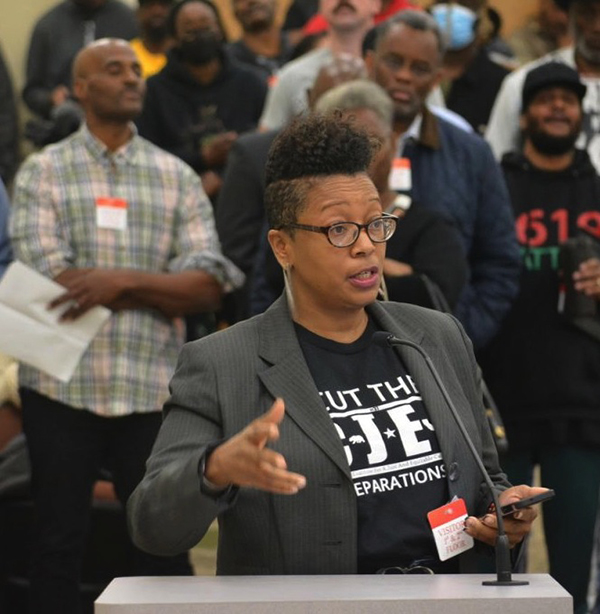

At a Women’s History Month ceremony hosted by Community Build and produced by Albert Lord, Community Build vice president for government relations and arts programs, City Councilwoman Heather Hutt presented the original founding members of the Black Stuntmen and Women’s Association with a certificate of appreciation for their contribution to the Black community and the Hollywood film and television industry.

The certificate was signed by Hutt, Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson and Councilman Curren Price.

“Today’s generation of Black female stunt workers stand on the shoulders of pioneers like Phyllis Ellis and Jadie David who paved the way,” Community Build President Robert Sausedo said. “Even though we have a long way to go in the entertainment industry, it’s important to acknowledge how we got this far.”