By Starlett Quarles

Contributing Columnist

As we approach the end of another Black History Month, I always end up asking myself, “With all that we’ve contributed to the evolution of this country, why do we continue to only celebrate and teach Black history in schools for one month? And why is it celebrated during the shortest month of the year?”

While the latter question is somewhat of a subjective and cynical complaint, I do feel my first question is worthy of some scrutiny. Now don’t get me wrong, I truly appreciated growing up with a month dedicated to learning about the historical contributions of my people. I mean that’s how I first learned about Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and that Garrett Morgan created the three-light traffic signal in 1923.

But as I got older and wiser, I began noticing that during every single Black History Month, we were still mainly discussing of course Martin, Malcolm and Harriet Tubman, along with a few additional inventors, like Madam C. J. Walker and George Washington Carver.

Sure, my knowledge base on our Black history would eventually expand from what I was being taught at home, on television shows like “Roots,” through my personal explorations and even throughout my educational career. It was then that I learned about different African kings and queens, Black Wall Street, Emmett Till, and that the Moors (Spanish and North African Muslims) discovered the Americas more than three centuries before Christopher Columbus.

But as it relates to this country’s educational and social acknowledgement, Black history continues to only be celebrated and intentionally taught during the shortest month of the year.

I am aware that last October, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 101 making California the first state to require all students to complete a semester-long course in ethnic studies in order to graduate from high school. And that this law is “the first mandate of its kind to ensure students are taught about ethnic and racial groups whose history and traditions have been traditionally overlooked,” as reported by the Washington Post.

That is, the course will not only teach Black history, but it would also include lessons on the American contributions of Latinos, Native Americans and Asian Americans, which The Post reports as “a model ethnic studies curriculum that more closely reflects the diverse population in California classrooms.”

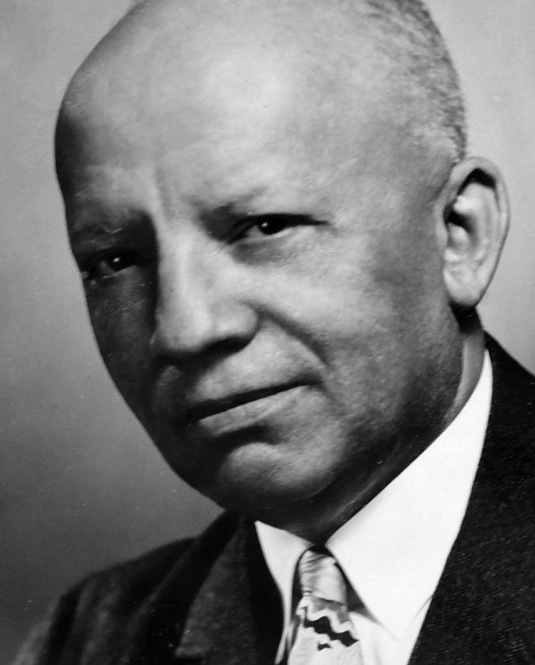

While I’d say this is “progress” and we’ve come a long way since Carter G. Woodson’s announcement of Black History Week in 1926, it’s still not an immediate or widely accepted solution.

Not only does this law take effect starting with the graduating class of 2029-30, but it’s also (not surprisingly) being met with much opposition. According to EdSource.com, “Parents in largely white, politically conservative areas are already pushing back on the mandate and mischaracterizing what’s in the model curriculum.” It’s even being described as racist and bigoted.

And for me, it’s an “ethnic” studies course, and not a mandated Black American history course. While I have no issue with the requirement to study the history of California’s diversity, my argument is for a more expansive focus on the contributions of Black Americans, before and after the Atlantic Slave Trade, and you just can’t teach that in 28 days.

But in all honesty, I will say in America’s defense, like the value of money, our history and culture is something that really should be first taught at home. We all know we live in a racist society, so in my humble opinion, it’s really our personal responsibility as a people to not only learn our history for ourselves, but to also cultivate that pride and teach this truth to our children.

We shouldn’t rely solely on the state or government to tell our story or honor our contributions to this country.

And although they may only teach or acknowledge our history in the month of February, America “celebrates” the contributions of Black Americans 365 days a year, whether they realize it or not.

When they transport food, blood or medicine in refrigerated trucks, they can thank Frederick McKinley Jones for his 1940 invention. Or when they push a button to get on an elevator, America can also thank Alexander Miles who invented the automatic elevator doors in 1887.

And ladies, thank God for Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner, the “Unsung Shero” who in 1957 patented the adjustable, moisture proof sanitary belt during the time when women were still using cloth pads for their menstrual cycles. The holder of five patents, Mary Kenner also invented a toilet tissue holder and a back washer that could be mounted on the shower wall. C’mon “Black Girl Magic!”

And lastly, before there was the Ring or ADT Home Security System, there was Marie Van Brittan Brown who in 1966 filed a patent for the first-ever home security system after wanting to increase the security in her Queens, New York home.

I can really go on and on about the numerous contributions Black Americans have made to this country. From historic inventions and patents to sociocultural transformations in science, medicine, and entertainment — just to name a few.

But in the end just know, there is no American history without Black history. And even though this country continues to acknowledge Black history for 28 days in February, it is ultimately our responsibility to make sure that we learn it, teach it, honor it, and protect it 365 days year, after year, after year.

Starlett Quarles is a Gen X Advocate, public speaker and host of the internet TV Talk Show, “The Dialogue with Starlett Quarles.” For more, please visit www.TheDialogueLA.com.