By Alfredo Santana

Contributing Writer

DOWNEY — For media producer Luis Dominguez, jobs filming weddings, baptisms and quinceañera ceremonies came to a screeching halt in March following the state and local orders banning large gatherings in an effort to contain the spread of the coronavirus.

Partnering with two other commercial tenants, Dominguez split three ways a nearly $1,500 a month rent for a three-room office located on the second floor of The Lakewood office building in Downey.

In early April, there were no signs that the virus would devastate his family and himself, but the virus hit him hard.

Dominguez contracted COVID-19 from his father-in-law and was quarantined for three weeks with headaches, back spasms and a cough.

The video maker was lucky and recovered, but his father-in-law died. Afterward, Dominguez picked up his Apple computer from the office, cameras, printers and other video hardware and vacated the room.

Coping with nonexistent film orders, Dominguez said he does not plan to return to the office soon, as his cash flow ran dry.

“I would want to comeback, that is the idea,” he said. “But I’m looking at that until the pandemic is controlled, and a vaccine is found. Before it, I would have an uncertain [work] situation.”

Reeling from two mandated lockdowns of nonessential business, many commercial tenants in the region are caught with diminished income streams that have hampered their ability to pay rent beginning in April and stretching into August.

Dominguez said two deferred months were recently covered, but the tenants still owed for June and July before August rent was due.

Aware of the crisis, area cities have embraced a mix of county and municipal measures such as commercial rent moratoriums that give tenants leeway to cover rent due since the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

Downey passed an ordinance that banned commercial evictions against renters who can document injury from the coronavirus, and gave two months per deferred payments starting in April. The moratorium expires Sept. 30.

However, the city can extend the moratorium if a high number of illnesses continue. Downey had reported 3,071 confirmed COVID-19 cases on Aug. 4.

County supervisors have extended until Sept. 30 a law that prohibits court evictions on businesses affected by COVID-19, but it only applies to cities that have not issued their own ordinances.

All moratoriums require tenants to document injury from the coronavirus to avoid being issued an unlawful detainer served by sheriff’s deputies, showing the reduced income or a combination of increased costs for sanitizing and purchasing supplies caused the unpaid rent.

Tenants are encouraged to explain the situation to their landlords with proof of reduced cash flow.

The county’s moratorium “may be extended by the board on a month-to-month basis, [and] implements a countywide ban on evictions for residential and commercial tenants,” according to a statement issued by the Board of Supervisors.

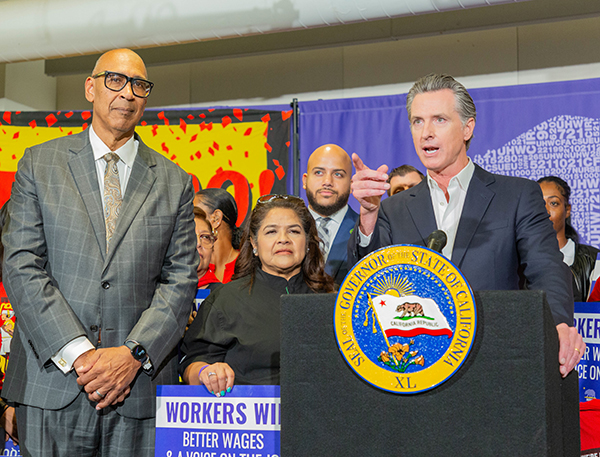

In March, California Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order that blocked the state’s Civil Code Sections 1940 and 1954 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited local governments’ ability to ban commercial evictions when rent nonpayment are grounds for eviction.

However, the order does not relieve tenants of paying deferred or past due rent.

Compounding the economic blow, a surge in coronavirus transmissions prompted Newsom to roll back reopenings in 30 counties on July 13, including Los Angeles, limiting outdoor services to hair salons, churches and restaurants, and forcing reclosures of bars and gyms.

To control the virus spread, office tenants must follow county and state mandates that ban more than 10 people gathered indoors, should enforce maintaining six feet of distance between customers, and require customers to wear face coverings while dispensing hand sanitizers.

If city and county inspectors visit and find a breach of health regulations, businesses can be fined or risk losing their licenses.

A document released by the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles said Maywood, Lynwood, Commerce, Pico Rivera, Whittier and Downey adopted their own eviction moratoriums to relieve commercial tenants struggling with the effects of the coronavirus.

In L.A. County, tens of thousands of small business operators are in peril because of less workload, lack of job orders and lower sales.

Paramount, Bell, Bell Gardens, South Gate, Norwalk and Huntington Park decided to follow the county’s regulations prohibiting unlawful commercial evictions related to the coronavirus.

So in light of the emergency, state Sen. Scott Wiener, (D-San Francisco) wrote SB 939, a law to stop commercial evictions during the health crisis and for 90 days after it is lifted, and give “eligible tenants” one year after the governor declares the emergency over to pay accrued rent.

But SB 939 ran out of steam at a hearing of the Senate’s Appropriations Committee on June 22, as the bill drew opposition from senators sympathetic with landlords and managers of commercial units who claim they have mortgages, taxes and maintenance costs that are hard to postpone.

Wiener’s communication director Catie Stewart said there is “no chance of” other initiatives or amendments that would tackle the commercial unit crisis until the new legislative session convenes in January, because all proposed bills for 2020 moved to the Assembly.

“SB 939 was killed. For the moment, there is nothing we can do,” Stewart said.

The unit Dominguez subleased is property of Goldstar Enterprises Inc., a real estate company managing three office buildings in Downey.

Owned by Joseph A. Gomez, the Lakewood building has several vacant units in its 27 offices for rent, and a tenant who wanted to remain anonymous said he witnessed two trucks moving out furniture from two units since the pandemic was declared.

Gomez did not return a phone request for an interview.

For his part, Dominguez said he was hired in June to film an event on July 25 after the state and county allowed businesses to reopen. But the job order was canceled following Newsom’s second mandate to shut down that prohibited parties and large gatherings.

Now he works at home on projects he and his brother Oscar had put aside from last year. Dominguez does not know if he will be able to continue his business.

“I don’t know what will happen. Right now it is very difficult to tell,” Dominguez said.