South L.A. homicide surge draws little attention as citywide rates fall: The Hutchinson Report

I don’t know what was more disturbing and exasperating about the murder, the killing itself or the seeming indifference in the community to it.

The murder in question happened Aug. 15 on one of the busiest corners in South Los Angeles. A major shopping center, retail stores and street vendors all crowd near the corner.

Somebody had to see or maybe even know something about the killing and perhaps even the victim who remained unidentified. I went to the street corner in question the day after and other than the brief footage of the report of the shooting I watched before I went to the site, it was business as usual there.

The homicide did something else. It cast an ugly glare on the chronic high murder rate in South L.A. According to Los Angeles Police Department figures, the homicide rate in Los Angeles in 2024 plunged to the lowest level in 60 years.

Unfortunately, that welcome plunge in killings throughout the city did not include South L.A. There was a small incremental drop in the rate but only small. In comparison to the rest of the city, South L.A. continued to be the city’s murder central.

The latest killing continued the well-worn and infuriating pattern that when someone is gunned down in a poor neighborhood it draws barely a public yawn and scant press mention. In times past, there were calls for city officials to put more muscle behind an anti-violence campaign in South L.A. That call must continue to be made.

But that still begs the question of why so many young Black and Hispanic males strap guns to their waists and wantonly kill or are killed by each other. Nationally, even as murder rates have dropped, the rate among Blacks is several times greater than among whites.

Even more astounding, if the Black murder rate was excised from the U.S. murder rate figures, the country’s murder rate would be comparable to the rock bottom murder rate in some European countries.

The brutal reality is that plopping more police on the streets, tough prosecutions, three strikes and mandatory sentencing laws, the death penalty and putting more than one million Blacks and Hispanics behind bars have done little to curb the carnage in South L.A. and other predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods nationally. Nor will simplistic calls for tougher gun control curbs, though they should be made.

L.A. has one of the toughest gun control statutes on the books and it hasn’t stopped the carnage.

Despite the pet theories of liberals and conservatives, Blacks and Hispanics aren’t killing each other because they are violent or crime-prone by nature, or solely because they are poor and oppressed. Or even because they are acting out the obscene and lewd violence they see and hear on TV, films and gangster rap lyrics.

The violence results from a combustible blend of cultural and racial baggage. In the past, crimes committed by Blacks against other Blacks were often ignored or lightly punished. Many studies have confirmed that the punishment blacks receive when the victim is white is far more severe than if the victim is Black. The implicit message was that Black lives are expendable.

This perceived devaluation of Black lives by racism encouraged disrespect for the law, and has forced many Blacks to internalize anger and displace aggression onto others.

Many young Black males have become especially adept at acting out their frustrations at white society’s denial of their “manhood” by adopting an exaggerated “tough guy” role. They swagger, boast, curse, fight and commit violent, self-destructive acts.

When many Black males indulge their murderous impulses on other Black males, they are often taking out their pent-up frustrations on those whom they perceive as helpless and hapless. This is a twisted and warped response to racism and deprivation, blocked opportunities, powerlessness, and alienation.

The other powerful ingredient in the deadly mix of violence in poor Black and Hispanic communities is the gang and drug plague. That further fuels the murder plague since innocent victims are often caught in their shootouts.

The answer to curbing the continued deadly cycle of murder violence in South L.A. is complex and defies any one-size-fits-all solution which again is usually simply demanding more police and jailings. It requires a coordinated effort by educators, health professionals, drug counselors, violence prevention specialists, gang intervention activists, victims of violence and local community activists and leaders, and, most importantly, parents to stem the violence.

They must devise and coordinate short- and long-term strategies and programs to provide jobs, training, better education, and boost the self-esteem of at-risk young people. Public officials must provide the political muscle and resources to implement these programs.

If there was a comparable high murder rate in West L.A. or the more affluent parts of the San Fernando Valley, the public and L.A. policy makers would declare a citywide crisis and rush to address it. The murder on the corner I stood on the day after the latest killing demands the same response.

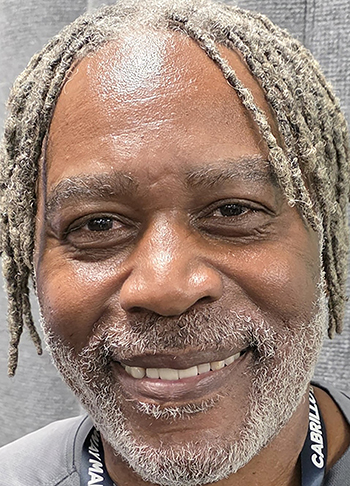

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is an author and political analyst. His forthcoming book is “Trump for Sale” (Middle Passage Press).