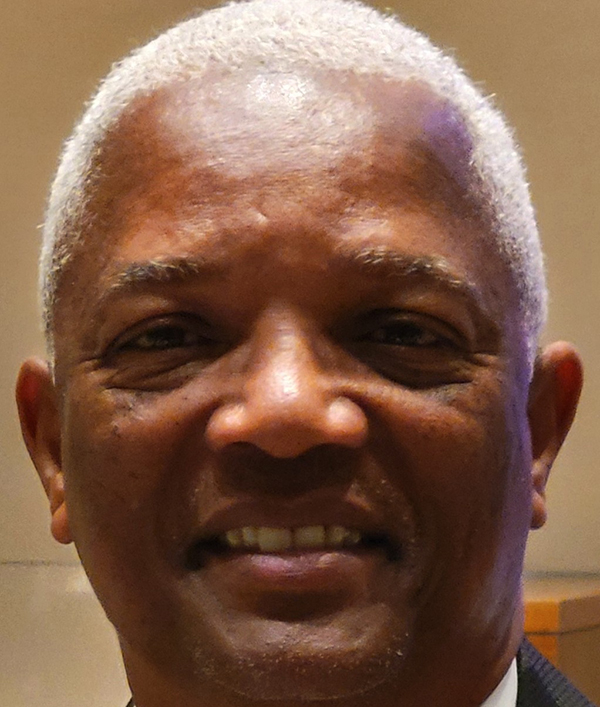

By Earl Ofari Hutchinson

Contributing Columnist

One doesn’t have to go far to find public spaces and places in Los Angeles that are named after racists or those who propagated racist acts and policies.

Crenshaw Boulevard, Leimert Park and Reuben Ingold Park in View Park are three. They are named after Walter Leimert, George Lafayette Crenshaw and Reuben Ingold.

These three familiar names were the major perpetrators of racially restrictive covenants on many homes in Leimert Park, Baldwin Hills, View Park and Windsor Hills. Yet, in a perverse back door nod to bigots and their bigotry, their names adorn these public spaces.

The few past attempts to remove their names have gone nowhere due to layers of legal entanglements that come with their names. The most recent is the call by this writer to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to remove Ingold’s name from Ingold Park and replace it with the name of an honored civil rights and social justice advocate.

The irony and insult are that the areas are now predominantly Black and minority, none of whom would have had a prayer of purchasing a home in these areas for the nearly three decades that the racially restrictive covenants that were slapped on the deeds of homes in the area remained enforceable and for more than a decade after they weren’t. Worse, they are still there by the thousands.

Surprise is too charitable a word to describe the feeling L.A. County Supervisor Holly Mitchell for one felt when she discovered that a relative’s Exposition Boulevard home had a racially restrictive covenant baked into it. The covenant was straightforward. It prevented the sale of the home to Blacks. Shock at this finding was the better word to describe her feeling at this discovery.

Mitchell wasn’t alone. Thousands of homeowners and would-be homeowners have found the same racially restrictive covenants in their deeds, too.

The racist covenants were tossed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 as unenforceable. The 1968 Fair Housing Act rendered them illegal.

Twelve states, including California, and Los Angeles County have tasked homeowners and officials to comb homeowner deeds and strike any racial exclusion language from them.

But there’s another problem, in fact two problems. One is how they got there in the first place. The other is that they are still there.

Leimert, Crenshaw and Ingold bought land, parceled out tracts and oversaw the home building craze in new subdivisions from the 1920s through the 1940s in the Crenshaw District.

Their models for success rested on two simple ideas. One was to make the area an upscale, toney, garden spot for homebuyers. The other was to make sure those buyers were white.

The “whites only” area that they envisioned and would back up with the force of law, public policy and solid white homeowner support lasted for nearly three decades. The white-only barrier was so unyielding that Black entertainers, athletes and businesspersons, no matter how wealthy, knew that buying a home in Lemert Park, Baldwin Hills and View Park-Windsor Hills was off-limits to them.

In 1948, the Supreme Court finally declared the racially restrictive covenants were not enforceable. However, a high court ruling was one thing, enforcing it was another. For nearly a decade after the court ruling, those areas remained almost exclusively a whites-only area. White homeowners used a myriad of subterfuges and dodges to ensure that no Blacks bought homes.

However, the first trickle of Black homebuyers began in the mid-1950s. By the 1960s, white flight was in full stampede mode. The neighborhoods, then, as other previously all-white neighborhoods in other cities, quickly turned from all-white to mostly Black.

Despite the change, many of the Black homeowners still noted that the racially restrictive covenants that had been imposed for decades by Leimert, Crenshaw and Ingold still were in their property deeds. They weren’t enforceable. But they were still there.

Some took this as simply a reminder of a hideous by-gone past in which Blacks were deliberately and legally kept out of the area while being walled into the oldest, most dilapidated and worst kept areas of South Los Angeles with the highest unemployment, poor public services and miserably, underserved failing public schools.

They were wrong. The racially restrictive covenants were anything but a product of a far-gone past. They are the foundation of a very real and very present racially engineered and subtly maintained home crisis of today.

Repeated studies have found that Los Angeles is still one of the nation’s most racially segregated cities, with a big, largely Black and Latino Central and South part of the city ringed by upscale white middle-class neighborhoods. The deeds on the homes in these areas do not, and can’t, have any racial restrictions on their sale.

However, they don’t need them. Price, neighbor attitudes and location do the trick of ensuring that the neighborhoods stay all or mostly white.

This in effect accomplishes Leimert, Crenshaw and Ingold’s vision of exclusive, insular, upscale, preferably white’s only neighborhoods.

Calls to rename places such as Ingold Park can’t be separated from the battle to scrub the names of Confederates and others off monuments and public places who propagated racial hate, bigotry and division. That is why it is past time to take Ingold and the names of our home-grown bigots off public spaces and places in our neighborhoods.

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is an author and political analyst. The new YouTube documentary “American Journalist” chronicles his decades long writing and activism. He also is the host of the weekly Hutchinson Report on KPFK 90.7 FM Los Angeles and the Pacifica Network.