By Darlene Donloe

Contributing Writer

WATTS — Billy Mitchell knows the benefits, importance and opportunities available to kids who are professionally trained in music.

There are numerous music competitions and scholarships offered to Black students each year but Mitchell, a veteran jazz musician, discovered very few, if any, Black students were submitting applications. His goal is to get the word out about the many opportunities that could possibly lead to some kids attending college or becoming professional musicians.

“It has become difficult to find an African-American youngster that can play a musical instrument,” said Mitchell, a married father of two grown sons. “I want to get the word out about these opportunities.

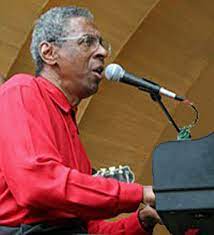

Puzzled and disheartened by the inability to locate qualified applicants, and the lack of interest Black students show toward music, Mitchell, a jazz pianist who has performed with performers like Randy Crawford, Esther Phillips, Linda Hopkins and Gloria Lynne, began his own crusade to inspire a new generation of musicians.

A passionate advocate of music’s ability to positively influence a child’s future, Mitchell has made it his mission to introduce music into the lives of as many children as possible.

In 2000, he launched the Scholarship Audition Performance Preparatory Academy (SAPPA) in an effort to make Black students aware of the availability of scholarships and to prepare and train them for competitions.

SAPPA introduces basic musical skills into communities with minimum or no music education opportunities.

The program focuses on areas with high percentages of at-risk youngsters who are often not able to afford formal music training.

SAPPA teaches music to kids ages 7 through 18, at all skill levels, and specializes in connecting talented youth with free professional training and mentors working in the music business.

Due to some families’ inability to pay, Mitchell, who studied political science at Morehouse College, made the after-school program tuition-free.

Today SAPPA, reportedly the only tuition-free music program in the South Los Angeles area, is conducted out of several locations including the Watts Labor Community Action Committee, Alma Reaves Woods Library, Macedonia Baptist Church, Siemon Community Center, Children’s Institute and Grant AME Church.

The program can accommodate up to 500 students. Mitchell, who is also a composer, said due to the pandemic, the program’s enrollment dipped to between 75-100 students. One-hour classes are offered twice a week between the hours of 4 and 6 p.m.

In 2012, Mitchell, born in Tarrytown and raised in Buffalo, New York, launched the Watts-Willowbrook Academy, a music workshop program designed to transform the lives and minds of youth in underserved communities through music training and personal development.

Formally the Watts-Willowbrook Conservatory, it was established as a project of SAPPA. The non-tuition symphonic string program provides music training in all orchestral string instruments, including the violin, viola, cello and upright bass.

“I’ve seen how the music and the experience have helped kids develop in a number of ways,” said Mitchell, who is married to jazz pianist Yuko Mabuchi. “Music makes you a better person. That’s my main motivation.”

I recently asked Mitchell to talk about his efforts.

DD: Why do you care so much about the kids learning music?

BM: The first thing is, I know how important music and art is in a young person’s development. When they don’t have that, they are losing a big part of their education. There is a lot of humanity involved in the arts. There is a spiritual value to music.

DD: What have you witnessed that tells you to continue with your efforts to get kids involved with music?

BM: I’ve seen how the music and the experience have helped kids develop in a number of ways. Music makes you a better person. That’s my primary motivation. There are so many opportunities waiting for our kids. They can learn an instrument and they can go to college. A lot of the time society stresses involvement in sports — that’s a problematic percentage. With music, there is an opportunity.

DD: Why is your focus on Black children?

BM: My focus is for children but Black children are the lowest denominators when it comes to being in the arts.

DD: Why don’t we see Black kids in the arts?

BM: Because they are not being taught. They are not taking advantage of the opportunities. The culture has not been welcomed in the orchestras. We don’t really support our own as a group. We are not encouraging our kids. We all have issues in our communities to just survive. We don’t have two[or] three cars, and mom and dad at home. Our kids have a hard time even getting to the program. Economic inequities have a lot to do with it. That’s why we fight to make these programs available.

DD: When did you take up this fight?

BM: I’ve been fighting this for more than 10 years now. Shocking to me how little the media pays attention to what our kids are facing. We don’t put emphasis on things that are crucial at this point. We don’t even have a good understanding of what music is. We are in a crucial era right now with our young people.

DD: What do you think will happen to Black kids if they are not in the arts?

BM: They will be consumers. They will be sitting and watching other people make the money. You have to have an understanding of music basics to do hip-hop. Take a piano class to learn what a whole note is. There’s a lot to know.

DD: What are they learning?

BM: Music that can be applied to anything. Then they can decide what kind of music they want to play. You have to have a basic understanding. You need to learn how to read notes and drum beats. It makes you more comfortable and creative. You’re not counting on a machine to give you chords. The creative mind is a lot more exciting and entertaining than the copied mind.

DD: What percentage of the students that participate are Black?

BM: About 80-90% of the participants are Hispanic, we have a couple of Filipinos and the rest are Black. The percentage of boy participants is 10-20%, which means 80-90% are girls. Most of the kids are between the ages of 7 and 13.

DD: How have you been trying to get the word out about the program?

BM: Through emails and flyers and some radio shows in the past. I’ve gone to churches to speak. I just hired someone to do social media. We’ve been on Instagram and Facebook for a while. The kids in our area are not gravitating to instrumental music. Most that we get are because the parents saw the info. We need to build a better rapport with the community.

DD: Do you have support?

BM: For the last 20 years, some foundations have helped. The longest running has been the Herb Alpert Foundation and the California Arts Council. Other current sponsors include the Reissa Foundation, LA Arts Recovery Fund, Ray Charles Foundation, Partners in Music Learning, Colburn Foundation and the Lark Ellen Lions Charitable Foundation.

DD: When you came to L.A. in the 70s, you worked as a jazz musician almost exclusively in the many Black-owned venues throughout Los Angeles. Now, you say, there isn’t one left. Why did they close and do you miss it?

BM: That’s a good question. How did we allow it to happen? I played Freddie Jet’s Pied Piper, The Tiki Room and several others. Do I miss it? Yes, I miss it. I miss the vibe.

“The Q&A” is a feature of Wave Newspapers asking provocative or engaging questions of some of L.A.’s most engaging newsmakers or celebrities.

Darlene Donloe is a freelance reporter for Wave Newspapers who covers South Los Angeles. She can be reached at ddonloe@gmail.com.