Will Reparations Finally Be Paid to Displaced Families?

Almost seven decades after Los Angeles officials shamelessly displaced predominantly Latino residents of Chavez Ravine to build Dodger Stadium, a California legislator on baseball’s 2024 Opening Day called for reparations to correct ‘an injustice’ to those families.

By TONY CASTRO

In 1959, the last families were shamelessly driven out of a close-knit, mostly Latino neighborhood of winding canyons and brush-dotted hills with stunning views of the downtown skyline, that they knew as Chavez Ravine to make way for a new major league ballpark that would be called Dodger Stadium.

Rachel Cantu was a teary-eyed 10 when she watched her mother Aurora Vargas, after having a baby taken from her arms, being dragged by sheriff’s deputies down the steps of her home of nearly four decades and taken to jail.

Minutes later a bulldozer knocked the house down, the rubble from the home at 1771 Malvina Avenue buried under what today is only feet from the mound where Sandy Koufax later pitched his perfect game.

“I don’t have anything against the Dodgers — they’re our team,” recalled Cantu, still choking up when she talks about that May day in 1959. “It’s just the process by which they got here. My mom is the one they carried out of her house.”

Photographs of that incident have frozen that moment in time for many as an embarrassment of one of the most disappointing times in the history of Los Angeles as ambitious local officials did whatever they thought they had to do to bring a major league baseball team to the city, the poor and the powerless be damned.

“People who lived there would bury their babies’ umbilical cords in the dirt there, that’s how much the land meant to them,” says actor-filmmaker Ira Angustain, who was only nine months old when his family’s house was knocked down in 1959 but grew up sharing the passion and emotion of the moment passed on to him by loved ones.

“There’s a lot of memories and a lot of people hurt over it. I have a lot of family members who say they will never go to Dodger Stadium because of it.”

That was a feeling that was widespread for a while among many Latino Angelenos, especially during the Chicano civil rights movement of the 1960s. But with time, a successful Dodgers team, and the Fernandomania craze after 1979, those hard feelings dramatically softened. The Dodgers became their beloved Doyers to many.

And so only now, amid the culture wars reckoning and reexamination of how America has mistreated minorities has the resentment against the Dodgers resurfaced among some Latinos and those who lived around Dodger Stadium and were forced to relocate.

It was all part of a land grab by city officials that dated back nine years before the Dodgers arrived from Brooklyn in 1958. As Los Angeles entered the 1950s, officials devised a plan to raze the poor, semi-rural neighborhoods of Chavez Ravine — all occupying valuable land adjacent to downtown — and replace them with low-income public housing.

The land, located between the San Gabriel Mountains and downtown Los Angeles, is widely known today as Chavez Ravine, but it was once the home to the Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop communities.

About 1,800 families, many of whom were Mexican American, lived there but were displaced in the 1950s after the city said the land was needed to build affordable housing, known then as the Elysian Park project.

Residents were forced to sell their homes for what they complained were below-market prices and promised first crack at the new housing.

That never happened.

Instead, in 1958 voters approved a measure to trade 352 acres of land at Chavez Ravine to the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Walter O’Malley, to attract the team to Los Angeles.

The Dodgers left Brooklyn for Los Angeles that year, and the construction of Dodger Stadium began, with the facility officially opening in 1962.

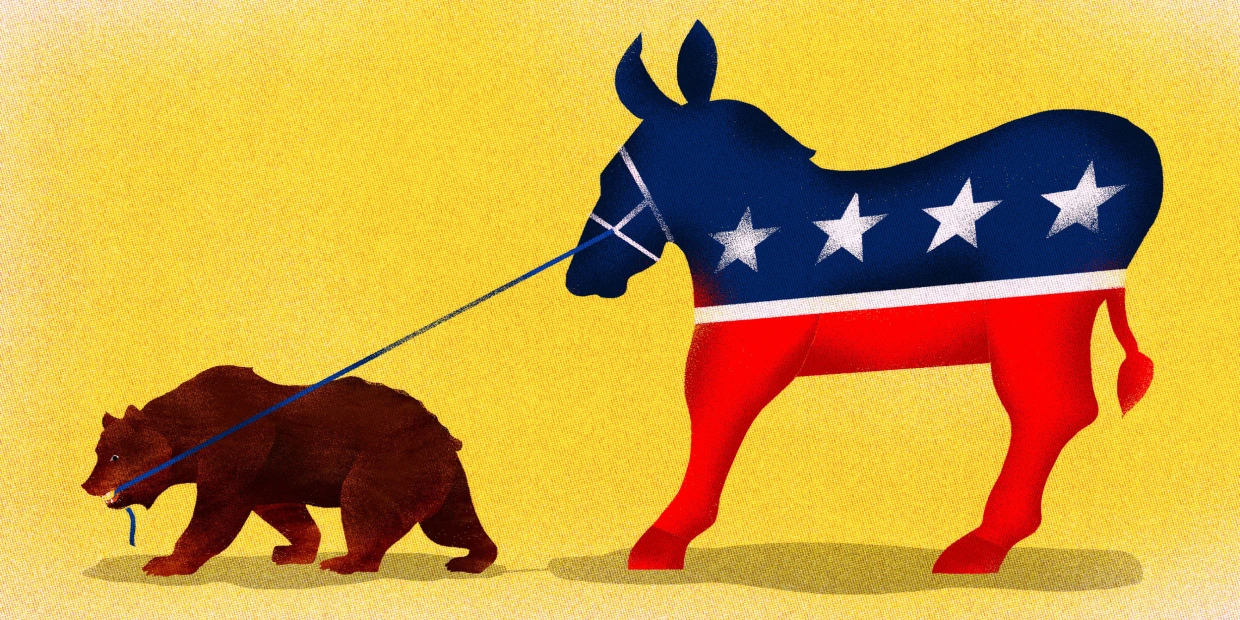

Last week, on Major Leagues Baseball’s official Opening Day, a Latina California legislator called for reparations to correct “an injustice” to those families who were displaced for the creation of Dodger Stadium — and introduced the Chavez Ravine Accountability Act, or AB 1950.

“In the 1950s, the vibrant communities of Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop were home to mostly Mexican American, as well as Italian American and Chinese American, families (who) saw an upheaval as they were uprooted and displaced in the name of progress with false promises of housing,” Assemblywoman Wendy Carrillo D-Los Angeles, told a news conference.

She held her news conference at the Elysian Park’s Los Desterrados (The Uprooted) Historical Marker that recognizes those displaced families from the communities that came to be known as Chavez Ravine, named after Julian Chavez, a rancher who served as assistant mayor, city councilman and eventually as one of the county’s first supervisors.

“Families were promised a return to better housing, but instead they were left destitute,” Carrillo charged.

According to Carrillo, her bill would result in what she described as “historical accountability” by creating a public and searchable database detailing events surrounding the land acquisition.

As for the families displaced for Dodger Stadium, and their descendants, news of the reparation legislation was a welcomed relief.

“You never think these things are going to come,” said Vincent Montalvo, whose grandparents lived in Palo Verde before they were also displaced. “This wasn’t something of a fairy tale, but now we’re going to be able to dive in deep with the bill as written of getting a lot of the history out.”

The the bill would require the database of former Chavez Ravine residents to be ready by Jan. 1, 2027, and the database would be needed before any compensation process could begin.

“It’s not over, but it makes it a little bit more real,” said Aurora Vargas’ niece, Melissa Arechiga, who founded Buried Under the Blue, a nonprofit that seeks to raise awareness about the history of the displacement of area residents.. “It verifies that all the hard work wasn’t for nothing.”

But both Arechiga and Montalvo said they would like to see changes to the bill, including having the Dodgers involved in the reparations because the bill currently does not include any participation by the Dodgers nor Dodger Stadium.

“Some of this has to come from the Dodgers, too,” said Montalvo, “because they’re still benefiting from the land, and they’re still profiting off our lands.”

The bill outlines various forms of compensation, such as offering city-owned real estate comparable to the original Chavez Ravine landowners, providing fair market value compensation adjusted for inflation and establishing a permanent memorial.

“What we seek to address with AB 1950 is knowledge, understanding and healing that is long overdue,” state Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara, a sponsor of the bill, said during the news conference.

Lara said the legislation offers an opportunity to address the wrongdoings, and the bill will serve as a “vehicle for reconciliation and healing for all residents of Los Angeles, including the Los Angeles Dodgers.”

“I grew up housing insecure in L.A. and grew up with the story of what happened to the residents of La Loma, Bishop and Palo Verde,” said Alfred Fraijo, founder and CEO of the law firm Somos Group, which has assisted in developing the reparations bill. “It was part of our cultural identity in some ways, a part of our own shared stories of discrimination and invisibility.”

“As a country, we have yet to officially account for how this hostility has limited the economic prosperity of so many people of color.”

TONY CASTRO, the former award-winning Los Angeles columnist and author of “Chicano Power” (E.P. Dutton, 1974), is a writer-at-large with Wave Newspapers. “Chicano Power” will be republished in a 50th anniversary edition in 2024. He can be reached at tony@tonycastro.com. Website: https//tonycastro.com