By Alfredo Santana

Contributing Writer

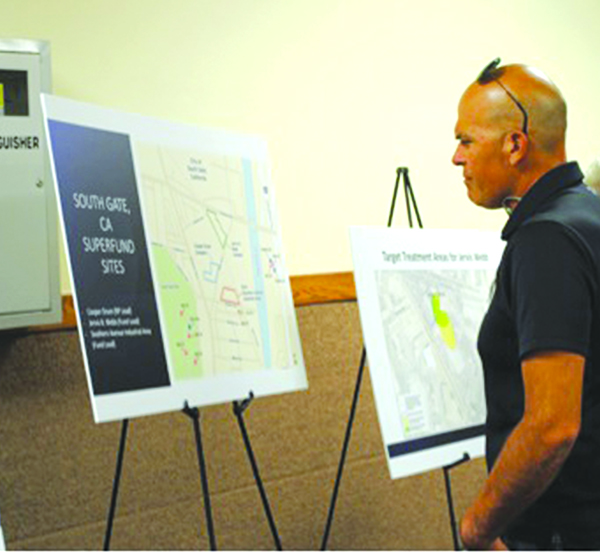

Two of three former industrial parcels in South Gate with high levels of underground contamination are being targeted for thermal decontamination as part of Superfund cleanups by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The Jervis B. Webb site, located at 9301 Rayo Ave. and at 5030 Firestone Blvd., contains dangerous amounts of tetrachloroethene (PCE), and trichloroethene (TCE) that spilled underground during the manufacturing of conveyor systems from the 1950s through 1996.

An adjacent building was also used to manufacture aluminum and stainless-steel aircraft rivets with wastewater and sulfuric acid that drained below the surface.

And the Southern Avenue Industrial Area site, found at 5211 Southern Ave., is contaminated with pollutants like cis-dicholoroethene (DCE) and trichloroethene blamed for tainting soil, groundwater and soil gas at least 30 feet underground.

Remedial project manager Sharissa Singh said at a July 14 presentation at the South Gate City Park Municipal Auditorium that underground chemicals at the Southern Avenue site were used to manufacture tapes to glue carpets.

The proposed cleanups would involve a process called “In situ thermal remediation” to remove hazardous chemicals in damaged soil and groundwater by applying heat.

The project manager also estimated the cleanup work would cost an estimated $11 million for soil, and about $17 million for groundwater per site.

Of those amounts, 10 percent would be covered by the state.

She underscored that most contaminated soils are found at depths where humans cannot be exposed, and impacted groundwater is not pumped for human consumption.

“Most pollution is at 50 to 60 feet of depth,” Singh said. “It’s unlikely the public will come in contact with it,”

The event drew South Gate residents pressing for faster and effective cleanups to make the properties fit for residential developments.

Mario Dominguez asked Singh to implement a remediation plan that allows the sites to be considered for multi-housing buildings in light of less availability of properties that meet such criteria.

He also blamed the agency for ignoring the plight of working-class communities for decades, and suggested the sites would have been remediated if they had been located in whiter, more affluent neighborhoods.

Singh replied the proposed plan is less expensive, more pragmatic and meets decontamination metrics for lots in residential zoning.

Thermal decontamination is so efficient that “99.9% of all underground pollutants are removed” after a year of continuous treatment,” she said.

Working in tandem with California regulators means any source of groundwater not used for drinking should be treated as such and cleaned.

The agency’s goal is to control and eliminate the identified contamination spots before chemicals spread to adjacent properties and create further damage, EPA staff said.

If the public supports the touted cleanup model, the environmental agency will move forward with blueprints and seek contractors able to develop the complex infrastructure.

They would be tasked with installing a web of underground poles to irradiate heat for a year, ensure a utility company provides a steady stream of power, and adapt equipment to capture vapor to decontaminate it before being released to the atmosphere.

According to Rusty Harris-Bishop, EPA’s region 9 manager, in situ or on-site thermal treatments have been selected for environmental cleanups in Oakland and Maywood, rendering positive results.

“We have to take it to the max level of soil cleanup for residential living,” Harris Bishop said. “Otherwise soil fumes would kill us.”

In situ thermal methods work better to remove chemicals in silty or clayed soil, the type of underground composition found in South Gate, and perform better compared to others because they reach contamination deep underground including beneath buildings, he said.

Applying heat to boiling temperature makes dirty chemicals move along soil and groundwater toward wells where they are collected and piped out to be neutralized.

Many chemicals are destroyed underground in the heating process.

Once the cleanup method is confirmed and contractors run job estimates, the agency will compile a comprehensive study to present in November in Washington, when the yearly period for fund allocations kicks off.

Harris-Bishop said they will compete for funding from a $5 billion pot created by the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to address cleanup sites across the country.

He said the proposed plan is based on scientific investigations and risk assessments documented during the superfund process.

Funding for the targeted parcels is way ahead of likely competitors such as the controversial Exide Technologies cleanup site in that soil sampling and toxicology analysis have been completed along with several remediation alternatives.

Perhaps the main differences between the South Gate sites and the proposed Exide Technologies’ is that funds from the state are already channeled to remove and replenish shallow soil on properties, and the size and scope of each.

“We have 20 years investigating and getting them documented,” Harris-Bishop said. “Any [superfund] site goes through a similar process. [Special funds are streamlined] only when emergency actions are taken like on landfills and abandoned sites.”

Monserrat Hidalgo, a South Gate High School student who attended the evening presentation, urged Singh and her staff to be more proactive on the matter, aware this is the first public event in three years to discuss the clean-ups since the COVID-19 pandemic postponed the process.

“Environmental justice is the issue,” Hidalgo said. “There are not that many communities with so many superfund sites” part of the same city.

Singh said the gathering was organized to update residents with the preferred cleanup method and to encourage them to write comments on the pitched cleanup choice through July 31.

Feedback collected online at singh.sharissa@epa.gov would influence the decision to move forward with the cleanup alternative, Singh said.

Public comments can also be mailed at U.S. EPA, Region 9, 600 Wilshire Blvd., suite 940, Los Angeles, CA. 90017.

“We are committed to preserve human life and the environment,” Singh said. “We are committed to implement it as soon as we can.”