By Earl Ofari Hutchinson

Contributing Columnist

May 25 marks the third anniversary of the slaying of George Floyd by then-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

The passage of time and the date are important for two reasons: One, it is the month that ex-Marine Daniel Penny killed homeless and mentally challenged Jordan Neely to death in New York; two, it was the deadly chokehold that caused Neely’s death, igniting rage, anger and a national debate once more on the use of the chokehold and its consequences.

Editor’s Note: This column is the first in a two-part series examining the continued deadly use of chokeholds by law enforcement and vigilante citizens. It is an excerpt from Earl Ofari Hutchinson’s new book, “The Chokehold” (Middle Passage Press).

Fueling the debate, is the fact that the victims of the chokehold have been almost all African-American men. The chokehold has every appearance of being a racially skewed, lethal tactic targeting Black men.

Following the death of Eric Garner in 2014, some police departments publicly declared that they did not use the chokehold. They cited inter-departmental regulation after regulation to prove that they barred the use of the hold, didn’t teach it to officers and many officers themselves said they wouldn’t know how to use it anyway.

That part, namely teaching the proper use of the technique, was certainly true. However, the chokehold is still in widespread use in police departments. It has many vigorous defenders who give a litany of reasons why the chokehold is supposedly a vital weapon in law enforcement’s arsenal.

One police department, though not American, has a long and storied reputation as a model of police efficiency. That is the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. It, too, was concerned about the potentially deadly effect of the use of the chokehold.

In June 2020, one month after Floyd’s death, the RCMP commissioned a study on the use of the chokehold. In the meantime, it decided not to bar use of the maneuver.

It presented stock reasons police officials gave for its continued use. The first was to assure that the chokehold was used only when there was the threat of grave injury, or bodily harm to the officer or someone else.

The second reason was that the department, mindful of Chauvin’s placement of his knee on Floyd’s neck in the infamous video of Floyd’s murder, took great pains to insist it did not teach or endorse any technique where officers put a knee on a suspect’s neck or head. RCMP officials were careful to say that the department used the chokehold in only a tiny number of cases.

The number they cited, though, was much too small to determine if a neck restraint, whether used properly or not, was a safe technique to de-escalate an encounter.

It is a far different matter, though, with many U.S. police departments. The substantial number of lawsuits brought by victims of the chokehold against departments at various times over the years, before and after Garner’s slaying, show that some departments and officers do use the chokehold or a variant of it to subdue suspects.

The U.S. Supreme Court made that possible.

Four decades ago, in 1983, it could have ended the use of the chokehold. It didn’t.

It rejected a lawsuit by Adolph Lyons, a young African-American motorist who was subjected to a chokehold by an Los Angeles Police Department officer following a traffic stop.

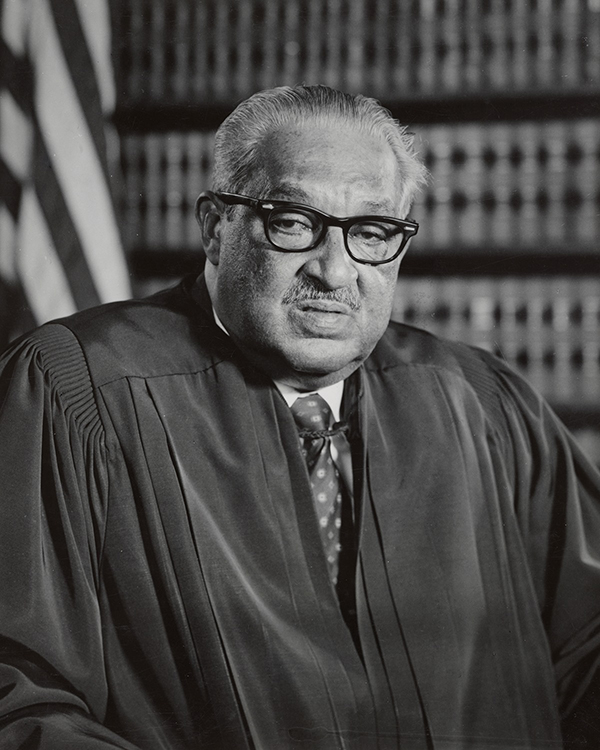

The court ruled in a 5-4 decision against sustaining an injunction that sought to bar its use. Justice Thurgood Marshall, in his dissenting opinion, was prescient about how the chokehold would cause much legal mischief in the decades to come: “Since no one can show that he will be choked in the future, no one — not even a person who, like Lyons, has almost been choked to death — has standing to challenge the continuation of the policy. The city is free to continue the policy indefinitely, as long as it is willing to pay damages for the injuries and deaths that result.”

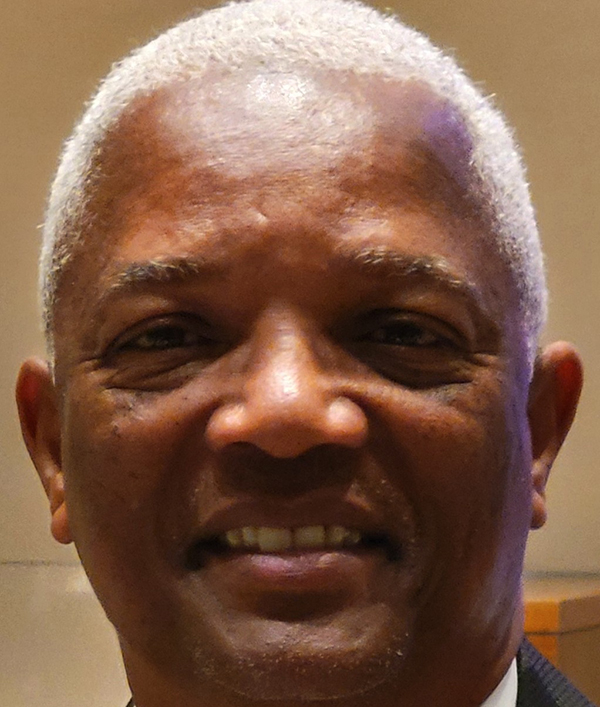

Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean of the School of Law at UC Berkeley agreed. In his book, “Presumed Guilty: How the Supreme Court Empowered the Police and Subverted Civil Rights,” he proved Marshall more than correct.

“To give one example,” he wrote, “George Floyd died in Minneapolis from police use of the chokehold. Eric Garner died in New York City from police use of a chokehold. Many others, especially Black men, have died from police use of the chokehold. One would wonder: Why hasn’t the Supreme Court said that the chokehold violates the Constitution, that there have been lawsuits trying to enjoin police use of the chokehold?”

This is the question that remains puzzling, frustrating and largely unanswered on the issue of police reform.

It’s a question that the Supreme Court and other courts have answered with their rulings and decisions to permit the continued use of the chokehold. It’s a question answered by many police departments in the U.S. that refuse to bar the use of the chokehold.

In the meantime, the Floyds and Neelys continue to be the victims of its use.

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is an author and political analyst. He is the host of the weekly Earl Ofari Hutchinson Show on KPFK 90.7 FM Los Angeles and the Pacifica Network Saturdays at 9 a.m.